Jag har – för stunden i varje fall – slutfört mitt projekt med att skapa en fullödig Wikipediaartikel om Jesus hos Josefus. Till den tidigare artikeln om Testimonium Flavianum (också publicerad på denna blogg i två delar här och här) har jag nu lagt till om ”Brodern till Jesus som kallades Kristus, vars namn var Jakob”. I samband därmed bytte jag också namn på artikeln från ”Testimonium Flavianum” till ”Jesus hos Josefus” emedan ”Testimonium Flavianum” inte längre speglar artikelns fulla innehåll.

Jag har försökt ta bort de 248 första fotnoterna eftersom de hör till den del (Testimonium Flavianum) som föregår denna del av artikeln, men då räknas allt om så att numreringen börjar från 1 och inte stämmer med artikelns numrering. Med andra ord ska man bortse från dessa första 248 fotnoter och börja från 249.

2 Brodern till Jesus som kallades Kristus, vars namn var Jakob

- 2.1 Texten i översättning

- 2.2 Argument till stöd för äkthet

- 2.3 Argument till stöd för förfalskning och allmänna resonemang

- 2.3.1 Invändningar mot äkthetsargumenten

- 2.3.2 Om Testimonium Flavianum är tillagt, så ock Jesus i Jakobpassagen

- 2.3.3 En marginalanteckning som av misstag kom att infogas

- 2.3.4 En annan Jakob

- 2.3.5 Sex skäl till varför det är en oavsiktlig interpolation

- 2.3.6 Hegesippos skildring av Jakob den rättfärdiges död

- 2.3.7 Origenes vittnesmål om Jakob

- 2.3.8 Eusebios vittnesmål om Jakob

- 2.3.9 Teorin om hur interpolationen uppkom

Brodern till Jesus som kallades Kristus, vars namn var Jakob

Den andra gång som Jesus omnämns hos Josefus är i den tjugonde och sista boken av Judiska fornminnen (20.9.1 eller 20:197–203). Bakgrunden till denna berättelse är att den dåvarande prokuratorn över Judeen, Porcius Festus (från ca 59–62), avlider. I det vakuum som uppstår innan den nye prokuratorn Lucceius Albinus (från 62–64) hunnit installera sig, passar den judiske översteprästen Ananos ben Ananos på att avrätta ”brodern till Jesus som kallades Kristus, vars namn var Jakob, och några andra”. Detta får till följd att Ananos avsätts som överstepräst och att Jesus ben Damneus utses till ny överstepräst.

Texten i översättning

| ” | Festus var död, och Albinus fortfarande på väg; så han [Ananos] inrättade ett råd av domare och lät inför detta föra brodern till Jesus som kallades Kristus, vars namn var Jakob [eller: ”Jakob hette han”], och några andra. Dessa dömde han såsom lagbrytare, varefter han överlämnade dem till att stenas. Men de medborgare som syntes rättrådigast, och kände sig mest illa till mods inför lagöverträdelserna, ogillade det som skedde. De skickade också bud till kungen [Agrippa II] och uppmanande honom att meddela Ananos att inte agera så framöver, ty det han redan hade gjort kunde inte rättfärdigas. Ja, några av dem for också för att möta Albinus som befann sig på sin resa från Alexandria och påtalade för honom att det var olagligt för Ananos att sammankalla Stora rådet utan hans samtycke; varpå Albinus gick med på det de sade och i vredesmod skrev till Ananos och hotade med att bestraffa honom för det han gjort; på vilket kung Agrippa fråntog honom översteprästämbetet som han innehaft i endast tre månader och utnämnde Jesus, son till Damneus, till ny överstepräst.” (Flavius Josefus, Judiska fornminnen 20:200–203; fetmarkeringen av det centrala stycket är tillagd]]).[249][250] | „ |

Argument till stöd för äkthet

De allra flesta forskare anser att denna passage skrivits av Josefus, att denne berättar om avrättningen av Jesu broder Jakob och därmed att också frasen ”brodern till Jesus som kallades Kristus” är äkta.[251][252][253][254][255]

De huvudsakliga orsakerna till att man anser detta är till antalet fem.[256]

Stycket förekommer i alla handskrifter

- Stycket om Ananos och Jakob förekommer i alla handskrifter av Judiska fornminnen 20:197–203 och dessutom utan några betydande avvikelser. Det finns således inget textstöd för att det rör sig om ett senare tillägg.[257]

Citeras tidigt

- I början av 300-talet sammanfattar kyrkofader Eusebios av Caesarea innehållet i Judiska fornminnen 20:197–203 och citerar meningen om Jakob och Jesus (Kyrkohistoria, 2:23:22).[258] Vidare antas Origenes av vissa ha känt till denna passage redan på 240-talet eftersom han tre gånger hänvisar till att Josefus ska ha skrivit att Jerusalems fall och templets förstörelse var judarnas straff för att de dödat Jakob den rättfärdige, ”brodern till Jesus som kallades Kristus”.[259][260] Uttrycket ”brodern till Jesus som kallades Kristus” är identiskt med det som står i Judiska fornminnen 20:200,[261] men ingenstans i Josefus bevarade verk står att judarna skulle ha straffats till följd av det som gjordes mot Jakob.[262]

Språk och sammanhang

- Hela stycket, liksom omnämnandet av Jesus, passar väl in i det omgivande sammanhanget och språket avviker inte från det som anses typiskt för Josefus.[263][264] Såväl Jakob som Jesus omnämns bara flyktigt eftersom de inte spelar någon framträdande roll i berättelsen – vilket man kunde ha förväntat sig att de skulle ha gjort om en kristen person lagt till uppgiften.[265] Steve Mason skriver att några visserligen har ifrågasatt äktheten i denna passage, men att det utifrån språk och stil inte finns några skäl till ifrågasättande.[266]

Neutrala beteckningar

- Om en kristen person skulle ha förfalskat passagen borde denne inte ha använt så pass neutrala beteckningar på Jakob och framför allt Jesus. Man kunde hellre förvänta sig att personen, i likhet med hur kristna ofta annars uttryckte sig, skulle ha prisat Jakob[267] och kallat honom ”brodern till Herren” eller ”brodern till Frälsaren” i stället för ”brodern till Jesus”. Vidare kunde man förvänta sig att Jesus inte bara skulle ha benämnts den ”som kallades Kristus” utan den ”som var Kristus”.[268][269] Josefus identifierar för sina läsare på ett neutralt sätt vilken Jesus han avser.[270][271][272] En beskrivning av Jakob som en broder till Jesus förefaller vara en osannolik kristen interpolation, eftersom den exakta formuleringen Iêsou tou legomenou Christou inte förekommer i beskrivningarna av Jakob i den kristna litteraturen.[273]

Saklig redogörelse med icke-kristna föreställningar

- Även om denna skildring av Jakobs död avviker på flera punkter från kyrkans skildring av hans död, anses det ändå finnas tydliga likheter mellan berättelserna. Josefus anses ofta vara den som ger den mer trovärdiga skildringen. Om en kristen lagt till uppgiften om Jakobs stening borde han ha sett till att berättelsen stämde bättre med den kristna skildringen såväl vad gäller detaljerna som tiden (där bland andra Hegesippos anger att Jakob dödades år 67 eller år 70 i stället för som här år 62).[274] Dessutom talar den korta sakliga framställningen för att Josefus skrivit stycket. En kristen interpolation borde ha innehållit mer av den långa kristna legendariska skildringen.[275]

Argument till stöd för förfalskning och allmänna resonemang

Även om de allra flesta forskare anser att Josefus skrivit stycket om Jakob och Jesus, finns det de som betvivlar den saken.[276] Några av dessa anser att hela stycket är ett tillägg till det Josefus skrev. När Josefus beskriver Ananos i sitt första historieverk Om det judiska kriget (4:5:2, § 319–325) visar han honom högaktning medan han i det senare verket Judiska fornminnen (20:9:1, § 199) kallar honom dumdristig och hård. De ”häpnadsväckande” motsägande omdömena om Ananos i de båda versionerna utgör enligt Tessa Rajak en ”mycket stark” grund för antagandet att ”hela berättelsen om Jakob är en kristen interpolation”.[277] Andra anser att Josefus mycket väl kan ha ändrat uppfattning i tiden mellan det att hans båda historieverk skrevs.[278]

De flesta förfalskningsförespråkare anser dock att Josefus skrivit nästan allt och att endast de centrala orden är tillagda i efterhand, då antingen ”brodern till Jesus som kallades Kristus, vars namn var Jakob” eller ”brodern till Jesus som kallades Kristus” eller så bara ”som kallades Kristus”. Tilläggen kan antingen vara medvetet gjorda eller vara marginalnoteringar som kommit att infogas i den löpande texten av misstag.[279]

Invändningar mot äkthetsargumenten

Emot de fem huvudsakliga argumenten för äkthet anför Ken Olson

- 1) att det bara finns tre handskrifter innehållande böckerna 18–20 av Judiska fornminnen och att dessa är beroende av varandra;[280]

- 2) att Origenes troligen citerar någon annan källa än den text av Josefus som finns bevarad, och att Eusebios därmed är den förste att citera stycket om Jakob och Jesus som förekommer i den bevarade texten av Judiska fornminnen, samt att stycket sannolikt har Origenes och inte Josefus som upphovsman;

- 3) att om bara identifieringen av Jesus som Kristus är tillagd förlorar argumenten att språket är typiskt för Josefus och att stycket passar så väl in i sitt sammanhang att en kristen person inte gärna kan ha skrivit det, mycket av sin tyngd. Vidare anser Olson att det inte sant att stycket i sin helhet skulle vara skrivet på ett för Josefus typiskt sätt eftersom ordet Kristus inte är typiskt för honom. Tvärtom undviker han det ordet och det förekommer hos Josefus endast här och i Testimonium Flavianum;[281]

- 4) att kristna visst benämnde Jesus den som kallades Kristus[282] och att det inte fanns någon kanoniserad formel för hur man benämnde Jakob då denne kunde kallas såväl Herrens, som Frälsarens och Kristus broder, så varför inte Jesu broder?

- 5) att det faktum att inget förutom namnet Jakob och att denne stenades stämmer med den kristna skildringen av Jakobs död, tvärtom tyder på att Josefus verkligen skrev om en annan Jakob. Senare bara antog någon kristen person att den judiske historikern avsåg de kristnas Jakob och lade därför till en identifiering i marginalen som vid nästa avskrift infogades i texten.[283]

Carleton Paget skriver i en replik till Olson att det verkar ”omotiverat” att ”lägga sådan vikt” vid tiden för Jakobs död. Fastän skildringarna är “mycket olika” är de ”åtminstone överens om att Jakob stenades, även om han i Hegesippos skildring slutligen dödas med en valkares klubba.”[284]

Whealey menar att om Eusebios skulle ha fabricerat Testimonium Flavianum, såsom Olson föreslår, skulle han också ha skrivit om passagen om Jakobs död så att den stämde med de kristna föreställningarna. Varför lät han i så fall inte Josefus uppge att Jakob dödades just innan Vespasianus belägrade Jerusalem eller bevarade uppgiften om att dess fall var följden av det man gjorde mot Jakob?[285] Vidare anser Whealey att uttrycket “som kallades Kristus” visar på en distanserad hållning till Kristus och att det därför inte är något som en kristen person skulle skriva. Hon menar att motsvarande uttryck i Bibeln (ὁ λεγόμενος Χριστός) också uttrycker distans eftersom orden antingen läggs i munnen på icke-kristna eller används i förklarande syfte.[286] Carrier menar dock att sammanhangen visar att det var ett vanligt kristet och judiskt sätt att benämna Messias.[287] Enligt Whealey kunde Nya testamentets författare visserligen tala om bröder till Jesus, men hon menar att man senare tog avstånd från att Jesus hade bröder i och med att han fick en mer gudomlig och Maria en mer jungfrulig status.[288]

Orsakerna till att man anser att Josefus inte skrivit om Bibelns Jesus på detta ställe är flera.

Om Testimonium Flavianum är tillagt, så ock Jesus i Jakobpassagen

Liksom detta omnämnande av Jesus har använts för att hävda att Josefus måste ha nämnt Jesus tidigare i Testimonium Flavianum,[289] har de som betvivlar att Josefus skrev något alls av Testimonium Flavianum hävdat att han heller inte kan ha nämnt Jesus i samband med skildringen av Jakob. Orsaken är densamma som vad gäller Testimonium Flavianum – att en identifiering av Jesus som den som kallades Kristus vore otillräcklig och inte typisk för Josefus sätt att skriva. Omnämnandet förutsätter nästan att Josefus redan förklarat för läsaren vem denne Jesus som kallades Kristus var.[290][291][292]

Andreas Köstenberger anser dock att detta i stället tyder på att Jesus var så känd vid denna tid att en identifiering av honom som den Jesus som kallades Kristus vore tillräcklig och att yttrandet bara indikerar att hans anhängare, inte Josefus själv, ansåg att han var Messias.[293] Carleton Paget anser att vid den tid Josefus skrev hade beteckningen Kristus blivit ett namn på Jesus, inte bara en titel.[294]

En marginalanteckning som av misstag kom att infogas

Tacitus, Annalerna 15.44, i den äldsta bevarade handskriften, Codex Laurentianus Mediceus 68 II, folio 38r.

En annan Jakob

Josefus skulle enligt detta scenario ha skrivit om en annan Jakob än Jakob den rättfärdige, som ska ha varit Jesu broder. Han skrev då ursprungligen om avrättandet år 62 av ”brodern till Jesus, vars namn var Jakob, och några andra”, och den Jesus han avsåg var Jesus ben Damneus som bara några rader senare sägs ha utnämnts till ny överstepräst efter den avsatte Ananos.[300] Jesus och Jakob var bröder, söner till Damneus och utgjorde en rivaliserande falang till Ananos-falangen. Detta var orsaken till att Ananos passade på att avrätta den ene brodern när möjlighet gavs och att folket upprördes över denna orätta gärning. Följden blev att Ananos avsattes som överstepräst och som ytterligare bestraffning fick Jakobs broder Jesus efterträda honom.[301] Enligt detta scenario skulle således en notis gjord av en kristen som bara trodde att denne Jakob var Jesu broder, oavsiktligt ha letat sig in i den handskrift som Eusebios hade tillgång till och denna därefter fortsatt att kopieras.

Sex skäl till varför det är en oavsiktlig interpolation

Carrier hävdar vidare att argumenten emot att detta skulle vara en interpolation i samtliga fall, frånsett det att Origenes skulle ha känt till texten hos Josefus, endast riktas mot att det skulle vara en medveten interpolation. De har enligt Carrier ingen påverkan på argumenten till stöd för en oavsiktlig interpolation.[302]

De argument som åberopas till stöd för att ”som kallades Kristus” är ett oavsiktligt tillägg till Josefus text, är:

- 1) att uttrycket ”som kallades Kristus” är just sådant man kunde förvänta sig att en skriftlärd skulle notera i marginalen som en minnesanteckning åt sig själv eller som upplysning åt framtida läsare om var Josefus (enligt vad denne trodde) nämnde Jesu broder Jakob;

- 2) att ordvalet och denna korta participsats struktur är just sådant som brukade användas i marginalnoteringar – plus att Josefus, om han verkligen skrivit detta och dessutom tidigare Testimonium Flavianum, i likhet med hur han nästan alltid annars gjorde, borde ha återkopplat till det förra omnämnandet genom att ha skrivit exempelvis ”den Jesus som kallades Kristus som jag nämnde tidigare”.[303] Även om Josefus inte skrivit något alls tidigare om Jesus, kunde man förvänta sig att han åtminstone förklarade vem denne Jesus som kallades Kristus var och vad ordet Kristus betydde;

- 3) att frånsett den nödvändiga ändringen av kasus är uttrycket identiskt med Matt 1:16 (Ἰησοῦς ὁ λεγόμενος Χριστός) som handlar om Jesu familj; ett uttryck en kristen rimligen borde ha varit mer benägen att använda än vad Josefus varit;

- 4) att Jakob inte passar som kristen eftersom också andra sägs avrättas tillsammans med honom och att hans avrättning sägs uppröra många inflytelserika judar.[304] Ty om Jakob var kristen var sannolikt de övriga som avrättades också kristna och mänskligt att döma skulle då också de som upprördes sympatisera med kristendomen. Men om så vore fallet, varför straffade då de judiska och romerska myndigheterna (vilka hatade kristna) Ananos för det han gjorde mot kristna? Och varför har inte uppgiften att många fler kristna än Jakob avrättades vid samma tillfälle överlevt i den kristna versionen?

- 5) att inget i Josefus skildring, frånsett att denne Jakob avrättades genom stening (den normala judiska avrättningsmetoden),[305] stämmer med någon annan berättelse om den kristne Jakobs död;[306] och

- 6) att Origenes var ovetande om den passage om Jakob som förekommer i Judiska fornminnen 20:200. Med tanke på hans kännedom om Josefus, hade han känt till den om den funnits vid hans tid.[307][308]

Hegesippos skildring av Jakob den rättfärdiges död

Den kristne hagiografen Hegesippos (grekiska Ἡγήσιππος) levde mellan ca 110 och 180 vt. Hans verk Uppteckningar (grekiska Ὑπομνήματα) i fem band[309] är försvunnet men vissa fragment finns bevarade genom citat, framför allt hos Eusebios av Caesarea. Hegesippos skildrar Jakob den rättfärdiges död och låter berätta att denne Jakob störtades ner från templets takspets av fariseerna och de skriftlärda. Han överlevde dock detta fall och därför stenade man honom. Men han överlevde också steningen. Då tog en valkare, dvs. en filtmakare, en klubba och slog ihjäl honom.[310] Även Klemens av Alexandria ansåg att Jakobs död gått till på detta sätt.[311]

Det finns enligt Carrier och andra[312] inga paralleller mellan denna berättelse och den som återfinns hos Josefus, frånsett namnet Jakob (som var ett vanligt namn)[313] och att båda stenas (vilket var den metod judarna normalt använde vid avrättningar).[314] Enligt Hegesippos (och Klemens) är ingen överstepräst inblandad i händelsen, Jakobs död är inte följden av en dom i en rättegång och han är dessutom den ende som dödas. Hans död sker ytterst genom att han klubbas till döds och inte genom stening, även om båda givetvis kan sägas ha stenats. De som i Josefus berättelse upprörs över saddukén Ananos avrättning av Jakob är rimligtvis fariseer, medan det i Hegesippos berättelse är fariseerna som tar livet av Jakob. Dessutom skriver Eusebios direkt efter att han avslutat Hegesippos skildring av Jakobs öde, ”att även förståndiga judar ansåg att denna händelse förorsakat Jerusalems belägring genast efter Jakobs martyrdöd,[315] vilket om man ska tolka detta bokstavligt innebär att Jakob dog år 67 när Vespasianus styrkor invaderade Palestina eller år 70 när den egentliga belägringen av Jerusalem inleddes.[316]

Emedan interpolationsförespråkarna anser att skillnaderna mellan Josefus skildring och den kristna skildringen tyder på att Josefus avsåg en annan Jakob än den kristne Jakob, hävdar äkthetsförespråkarna att skillnaderna i stället styrker äktheten i Josefus text.[317] Carleton Paget anser det vara omotiverat att lägga sådan vikt vid tiden för Jakobs död och anser att Hegesippos sannolikt inte menade att det som skedde omedelbart efteråt ändå inte kunde ske sex år efteråt. Och namnen Jakob och att de båda stenades visar på en viss likhet i skildringarna.[318] Meier anser att de stora skillnaderna mellan berättelserna stöder att Josefus skrivit passagen eftersom en kristen förfalskare skulle ha anpassat berättelsen så att den bättre stämde med de kristna föreställningarna.[319][320] Dessa argument fungerar dock enbart om det handlar om ett avsiktligt tillägg.[321]

Origenes vittnesmål om Jakob

Vid tre tillfällen i två av sina verk skrivna någon gång åren 244–249[322] skriver Origenes att Josefus sagt att Jerusalem och templet ödelagts som hämnd för/till följd av vad judarna gjorde med Jakob, brodern till Jesus som kallades Kristus.[323] Innehållet i dessa tre stycken är likartat och i Mot Kelsos 1:47 skriver Origenes följande:

| ” | Ty i den artonde boken av Judiska fornminnen bär Josefus vittnesbörd om att Johannes var en döpare … Samme författare, fastän han inte trodde på Jesus som Kristus, sökte efter orsaken till Jerusalems fall och templets förstörelse. Han borde [då] ha sagt att sammansvärjningen mot Jesus var orsaken till att dessa katastrofer drabbade folket, eftersom de hade dödat den Kristus varom det profeterats. Fastän omedvetet, är han emellertid inte långt från sanningen när han säger att dessa olyckor drabbade judarna som hämnd för Jakob den rättfärdige, som var en broder till Jesus som kallades Kristus, eftersom de dödat honom som var mycket rättfärdig. (Origenes, Mot Kelsos 1:47)[324] | „ |

Uttrycket ton adelfon Iêsou tou legomenou Christou (brodern till Jesus som kallades Kristus) är identiskt med motsvarande uttryck i Judiska fornminnen 20:200, där översteprästen Ananos sägs ha avrättat ”brodern till Jesus som kallades Kristus, vars namn var Jakob”.[325] Men även om det i Judiska fornminnen 20:200 står exakt ”brodern till Jesus som kallades Kristus”, finns inget uppenbart övrigt i berättelsen som påminner om det Origenes säger att Josefus också skrev. Enligt Origenes skulle Josefus ha sagt att själva handlingen att döda Jakob (den rättfärdige) ledde till att Gud lät straffa judarna genom att ödelägga Jerusalem och templet. Något sådant textställe förekommer överhuvudtaget inte i Josefus bevarade verk, och Origenes säger heller aldrig var hos Josefus han ska ha läst detta.[326][327]

En vanlig ståndpunkt är att Origenes vid dessa tre tillfällen verkligen citerar Judiska fornminnen 20:200 och därmed bekräftar förekomsten av texten hos Josefus senast på 240-talet.[328][329] Orsaken är framför allt den exakta överensstämmelsen med Judiska fornminnen 20:200 vad gäller uttrycket ”brodern till Jesus som kallades Kristus”. Den förklaring som främst brukar ges till att det övriga Origenes omtalar inte enkelt återfinns hos Josefus, är att Origenes citerar Josefus i just meningen om Jakob och Jesus, men sammanfattar och parafraserar honom för det övriga och kanske tolkar in sådant som Josefus inte direkt skrivit.[330][331][332][333][334]

En annan möjlighet är att Origenes hade tillgång till en text av Josefus som inte överlevt.[335] Det skulle i så fall kunna vara en text som skrivits av Josefus. Eftersom kristna knappast skulle ha utmönstrat en sådan text i samband med att avskrifter gjordes, har det också föreslagits att det i stället var en interpolation som infogats i någon eller några handskrifter och som inte överlevde eftersom dessa handskrifter aldrig kopierades. Detta öppnar enligt G. A. Wells för möjligheten att också andra tillägg gjorts till Josefus böcker.[336]

En ytterligare annan möjlighet är att Origenes tog fel, mindes fel, och nämnda stycke inte alls förekom hos Josefus utan i stället hos Hegesippos.[337][338] Genom att namnen Josefus (på latin Iosepus, Ioseppus, Iosippus)[339] och Hegesippos (på latin Egesippus, Hegesippus)[340] var så snarlika har de ibland förväxlats.[341][342] Det finns också andra exempel på att Origenes tillskrivit Josefus saker som han synbarligen inte har skrivit.[343][344]

Origenes förväxling av Hegesippos och Josefus

Att Origenes skulle ha förväxlat Hegesippos med Josefus stöds enligt Carrier av

- 1) att det tydligt framgår av Hegesippos att han ansåg att Jerusalem förstördes till följd av att Jakob dödades,

- 2) att Hegesippos, i likhet med det Origenes tillskriver Josefus, kallar Jakob för ”den rättfärdige”,

- 3) att Hegesippos, i likhet med det Origenes tillskriver Josefus, säger att folket ansåg Jakob vara synnerligen rättfärdig,

- 4) att också Hegesippos säger att ”vissa ansåg att Jesus var Kristus”, samt

- 5) att namnen Hegesippos och Josefus bevisligen har förväxlats vid flera andra tillfällen.[345]

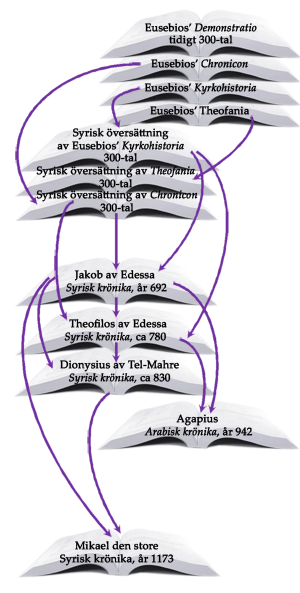

Eusebios vittnesmål om Jakob

Även Eusebios och Hieronymus återger samma passage om Jakob som Origenes.[346] Eusebios redogör i början av 300-talet för Hegesippos skildring av Jakobs död, säger att Klemens av Alexandria bekräftar denna (Kyrkohistoria 2:23:3–19)[347] och skriver direkt därefter:

| ” | Så underbar var Jakob och så omtalad av alla för sin rättrådighet, att även förståndiga judar ansågo att denna händelse föranlett Jerusalems belägring strax efter Jakobs martyrdöd: denna hade drabbat dem av ingen annan orsak än på grund av den mot honom förövade blodsskulden. Ja, Josefus har icke tvekat att skriftligt betyga detta genom följande ord: ”Detta hände judarna som hämnd för Jakob den rättfärdige, som var en broder till Jesus som kallades Kristus, eftersom judarna dödade honom, ehuru han var en mycket rättfärdig man.” Josefus berättar om hans död i 20:de boken av sin Fornhistoria med dessa ord: (Eusebios, Kyrkohistoria 2:23:19–21; i översättning av prof. Ivar A. Heikel)[348] | „ |

Därefter följer skildringen av hur Ananos avrättar Jakob såsom berättelsen nu föreligger i Judiska fornminnen 20:200. Eusebios säger att ”Jerusalems belägring … hade drabbat” judarna ”på grund av den mot honom [Jakob] förövade blodskulden.” Flera tolkar detta som en anspelning på det Hegesippos skrivit.[349] Sedan säger Eusebios att även Josefus påstår detsamma och återger, bortsett från en anpassning av de inledande orden, exakt det Origenes skriver i Mot Kelsos 1:47. Därefter återger han den bevarade passagen från Judiska fornminnen 20:200 och skiljer därför på dessa två redogörelser hos Josefus om Jakob.

Här finns således två möjligheter, antingen att både Origenes och Eusebios hade tillgång till en text hos Josefus som inte längre finns bevarad och att de båda citerade denna ordagrant,[350] eller att Eusebios citerade Origenes men uppgav att Josefus skrivit att Jerusalems förstörelse skedde som hämnd för Jakob den rättfärdiges död med förvissningen om att Origenes uppgift att så var fallet också var riktig.[351] Både Whealey och Mason ger exempel där Eusebios tillskrivit Josefus sådant denne inte skrivit på basis av uppgifter hos Origenes.[352][353] Jakob den rättfärdige är för övrigt en kristen beteckning och något som Josefus inte gärna kunde skriva.[354] Vidare skriver Josefus i sitt tidigare historieverk att Jerusalems ödeläggelse skedde till följd av idumeernas och seloternas härjningar och att mordet på Ananos ”var början på stadens ödeläggelse”.[355] Äktheten av den passage som Origenes och Eusebios tillskriver Josefus måste enligt Painter ifrågasättas, eftersom Josefus i det fallet hävdar att mordet på Jakob som iscensattes av Ananos var den utlösande faktorn för Jerusalems ödeläggelse, medan han tidigare hävdat att mordet på samme Ananos var den utlösande faktorn.[356]

Teorin om hur interpolationen uppkom

Följaktligen skulle enligt denna teori Origenes ur minnet ha parafraserat Hegesippos i tron att det var Josefus, men inte kunnat finna passagen hos honom (eftersom den inte heller nu existerar) och av den anledningen heller inte sagt var den förekom. Eusebios, som var föreståndare för det omfattande kristna biblioteket i Caesarea som tidigare skötts av hans lärare Pamfilos och före det grundats av Origenes,[357] hade sannolikt tillgång till antingen samma Josefus-handskrift som Origenes använde eller så en avskrift av densamma.[358] När Eusebios återger[359] samma passage som den Origenes återger tre gånger[360] (och då sannolikt citerar sig själv två av gångerna), kan han antingen (i likhet med vad Origenes i så fall måste ha gjort) ha citerat den ur en Josefus-handskrift,[361][362] eller så läst Origenes (vilken han var väl förtrogen med) och litat på dennes uppgift om att Josefus skrivit detta – trots att inte heller han fann motsvarande textställe hos Josefus.[363][364] Detta skulle förklara varför vare sig Origenes eller Eusebios angav var Josefus skrivit detta, trots att de som regel brukade uppge varifrån de fått sina uppgifter (författare, bok och ibland kapitel) och dessutom återger texten i ett sammanhang där de ger exakta referenser till andra passager hos Josefus.[365] Hieronymus byggde på såväl Origenes som Eusebios, varför även han sannolikt fått uppgiften om att Josefus sagt att ”Jerusalem förstördes på grund av mordet på aposteln Jakob” från någon av dem och inte från Josefus.[366]

Carrier menar att det var Origenes som skapade uttrycket genom att kombinera ett helt vanliga uttryck som ”brodern till Jesus” (som stod hos Josefus i Judiska fornminnen 20:200) med Matt 1:16 ”som kallades Kristus” i tron att Josefus någonstans skrivit något om Jakobs död, medan Origenes i själva verket hade läst det hos Hegesippos (Egesippus–Iosippus). Tack vare Origenes uppgifter kom någon (Origenes själv, Pamfilos eller någon annan) att föra in frasen ”som kallades Kristus” även hos Josefus i den handskrift av Judiska fornminnen som Eusebios senare skulle nyttja. Eusebios satt därför med två likartade uttryck, det ena hos Josefus och det andra hos Origenes. Han återgav därför båda textställena efter varandra med uppgift att Josefus skrivit båda, men angav bara var hos Josefus det ena förekom, eftersom han inte kunde hitta det andra. Med stöd av det Origenes och Eusebios skrivit och det som nu stod i Eusebios Josefus-handskrift, kom denna version att bli den som kopierades i framtida avskrifter av Judiska fornminnen.[367]

Referenser

Noter

- ^ Alice Whealey, Josephus on Jesus, The Testimonium Flavianum Controversy from Late Antiquity to Modern Times, Studies in Biblical Literature 36 (New York: Peter Lang, 2003), s. 1–5.

- ^ Bland dem som under de senaste årtiondena försvarat tesen att Josefus skrivit hela Testimonium Flavianum märks Étienne Nodet, ”Jésus et Jean-Baptiste selon Josèphe,” Revue biblique 92 (1985), s. 321–48 & 497–524; The Emphasis on Jesus’ Humanity in the Kerygma , s. 721–753, i James H. Charlesworth, Jesus Research: New Methodologies and Perceptions, Princeton-Prague Symposium 2007 (Grand Rapids, Eerdmans, 2014); A. Vincent Cernuda, “El testimonio Flaviano. Alarde de solapada ironia”, Estudios Biblicos 55 (1997), s. 355–385 & 479–508; och Ulrich Victor, “Das Testimonium Flavianum: Ein authentischer Text des Josephus,” Novum Testamentum 52 (2010), s. 72-82.

- ^ John P. Meier, ”Jesus in Josephus: A Modest Proposal,” Catholic Biblical Quarterly 52 (1990), s. 78.

- ^ Bland de under senare årtionden mer inflytelserika forskare som hävdat denna position kan nämnas John P. Meier, Steve Mason, Géza Vermès, Alice Whealey (som föreslår endast minimala tillägg), James Carleton Paget (som tror att Josefus skrivit något om Jesus men säger sig inse svagheten i ett sådant antagande: ”I am as clear as anyone about the weaknesses of such a position”, ”Some Observations on Josephus and Christianity”, Journal of Theological Studies 52:2 (2001), s. 603) och Louis Feldman (som ändå är öppen för att Eusebios skapat passage: “On the Authenticity of the Testimonium Flavianum Attributed to Josephus,” i New Perspectives on Jewish Christian Relations, ed. E. Carlebach & J. J. Schechter (Leiden: Brill, 2012), s. 26–27).

- ^ Bland dem som under de senaste årtiondena argumenterat för att hela Testimonium Flavianum är en kristen förfalskning märks Leon Herrmann, Chrestos: Témoignages païens et juifs sur le christianisme du premier siècle (Collection Latomus 109; Brussels: Latomus, 1970), s. 99–104; Heinz Schreckenberg, Die Flavius-Josephus-Tradition in Antike und Mittelalter, Arbeiten zur Literatur und Geschichte des Hellenistischen Judentums 5 (Leiden: Brill, 1972), s. 173; Tessa Rajak, Josephus, the Historian and His Society (Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1983); J. Neville Birdsall, ”The Continuing Enigma of Josephus’s Testimony about Jesus,” Bulletin of the John Rylands University of Manchester 67 (1984-85), s. 609-22; Per Bilde, ”Josefus’ beretning om Jesus”, Dansk Teologisk Tidsskrift 44, s. 99–135, Flavius Josephus between Jerusalem and Rome: his Life, his Works and their Importance (JSPSup 2; Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 1988), s. 222–223; Kurt Schubert (med Heinz Schreckenberg), Jewish Historiography and Iconography in Early Christian and Medieval Christianity, Vol.1, Josephus in Early Christian Literature and Medieval Christian Art (Assen and Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 1992), s. 38–41; Earl Doherty, The Jesus Puzzle: Did Christianity Begin with a Mythical Christ? (Ottawa: Canadian Humanist Publications), 1999, s. 205–222; Jesus: Neither God Nor Man – The Case for a Mythical Jesus, Ottawa: Age of Reason Publications, 2009, s. 533–586; Ken Olson, ”Eusebius and the Testimonium Flavianum,” Catholic Biblical Quarterly 61 (1999), s. 305–322; ”A Eusebian Reading of the Testimonium Flavianum” i Eusebius of Caesarea: Tradition and Innovations, ed. A. Johnson & J. Schott (Harvard University Press, 2013), s. 97–114; och Richard Carrier, ”Origen, Eusebius, and the Accidental Interpolation in Josephus, Jewish Antiquities 20.200”, Journal of Early Christian Studies (Vol. 20, No. 4, Winter 2012), s. 489–514; On the Historicity of Jesus: Why We Might Have Reason for Doubt (Sheffield Phoenix Press, 2014), s. 332-342.

- ^ Louis H. Feldman, Josephus and Modern Scholarship (1937-1980) (Berlin: W. de Gruyter, 1984).

- ^ Louis H. Feldman, ”A Selective Critical Bibliography of Josephus”, i Louis H. Feldman, Gōhei Hata (eds.), Josephus, the Bible, and History (Leiden: E.J. Brill, 1989), s. 430.

- ^ James N. B. Carleton Paget, ”Some Observations on Josephus and Christianity”, Journal of Theological Studies 52:2 (2001), s. 579.

- ^ Alice Whealey, Josephus on Jesus, The Testimonium Flavianum Controversy from Late Antiquity to Modern Times, Studies in Biblical Literature 36 (New York: Peter Lang, 2003), s. 31–33.

- ^ [a b] Robert E. Van Voorst, Jesus Outside the New Testament: An Introduction to the Ancient Evidence (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2000), s. 93.

- ^ Andreas J. Köstenberger, L. Scott Kellum, Charles L. Quarles, The Cradle, the Cross, and the Crown: An Introduction to the New Testament (Nashville: Broadman & Holman Academic, 2009), s. 107.

- ^ Louis H. Feldman, ”Introduction”; i Louis H. Feldman, Gōhei Hata, Josephus, Judaism and Christianity (Detroit 1987), s. 55–57.

- ^ Robert E. Van Voorst, Jesus Outside the New Testament: An Introduction to the Ancient Evidence (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2000), s. 83.

- ^ Översättningen är gjord av Bengt Holmberg och återfinns i Bengt Holmberg, Människa och mer: Jesus i forskningens ljus, 2., rev. uppl. (Lund: Arcus, 2005), s. 123. Samma text med endast den skillnaden att där står ”uppkallade” (vilket alltså senare korrigerats till ”uppkallad”) förekommer också i 1. uppl., Lund: Arcus, 2001, s. 132. Den text som i citatet är markerad i fetstil är i boken kursiverad och utgörs av det Holmberg anser vara ”kristna interpolationer”.

- ^ Grekiska originaltexten till Flavius Josephus, Antiquitates Judaicae, 18:63–64 (18.3.3) ”Perseus, Greek (Benedikt Niese, 1892)”.

- ^ Verket skrevs på grekiska och dess grekiska namn är Ἰουδαϊκὴ ἀρχαιολογία (Ioudaikē archaiologia). Det färdigställdes enligt Josefus under kejsar Domitianus trettonde regeringsår (Josefus Flavius, Judiska fornminnen 20:267). Detta svarar mot perioden september 93–september 94.

- ^ Codex Ambrosianus (Mediolanensis) F. 128 superior. Roger Pearse. ”Josephus: the Main Manuscripts of ”Antiquities””.

- ^ Eusebios återger stycket tre gånger; i Demonstratio Evangelica 3:5:104–106, i Kyrkohistoria 1:11:7–8 och i Theofania 5:43b–44 (bevarad endast i översättning till syriska).

- ^ Steve Mason, Josephus and the New Testament (2d ed.; Peabody: Hendrickson, 2003), s. 230.

- ^ Paul Winter “Excursus II – Josephus on Jesus and James” i The History of the Jewish People in the Age of Jesus Christ vol. I (trans. of Emil Schürer, Geschichte des jüdischen Volkes im Zeitalter Jesu Christi, (1901 – 1909), a new and rev. English version edited by G. Vermes and F. Millar, Edinburgh, 1973), s. 434.

- ^ Gary J. Goldberg, “The Coincidences of the Emmaus Narrative of Luke and the Testimonium of Josephus,” Journal for the Study of the Pseudepigrapha 13 (1995), s. 59–77. Se ”The Coincidences of the Emmaus Narrative of Luke and the Testimonium of Josephus, s. 2”.

- ^ Enligt Mason skriver Josefus som en ”passionerad förkämpe för judendomen” och han menar att det därför ”verkar vara omöjligt” att Josefus var kristen. Steve Mason, Josephus and the New Testament (2d ed.; Peabody: Hendrickson, 2003), s. 229.

- ^ Steve Mason skriver att eftersom grekiskans christos betyder smord och fuktad (”wetted”) skulle ett uttryck som att Jesus var fuktad ha tett sig helt obegripligt för den som inte var införstådd med det judiska Messiasbegreppet. Steve Mason, Josephus and the New Testament (Peabody: Massachusetts, 1992), s. 165–166; (2d ed.; Peabody: Hendrickson, 2003), s,227–228.

- ^ “Because Josephus was not a Christian, few people believe that he actually wrote these words [syftande på de messianska anspråken]; they may well have been added by scribes in later Christian circles which preserved his work. But the rest of his statements fit his style elsewhere and are most likely authentic.” Craig L. Blomberg, ”Gospels (Historical Reliability),” i Dictionary of Jesus and the Gospels, Joel B. Green, Scot McKnight, et al. (eds.) (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity, 1992), s. 293.

- ^ John P. Meier, A Marginal Jew: Rethinking the Historical Jesus, Vol 1: The Roots of the Problem (New York: Doubleday, 1991), s. 59–61, 74–75.

- ^ Eftersom språket är så pass likvärdigt i hela Testimonium Flavianum kan Alice Whealey argumentera för att i stort sett hela passagen är skriven av Josefus. Se Alice Whealey, ”The Testimonium Flavianum in Syriac and Arabic”, New Testament Studies 54.4 (2008), s. 588; Alice Whealey, ”Josephus, Eusebius of Caesarea, and the Testimonium Flavianum”, s. 95, 115–116, i Böttrich & Herzer, Eds., Josephus und das Neue Testament (Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2007).

- ^ “Hence, in the case of the three interpolations, the major argument against their authenticity is from content.” John P. Meier, A Marginal Jew: Rethinking the Historical Jesus, Vol 1: The Roots of the Problem (New York: Doubleday, 1991), s. 83, n. 42.

- ^ Géza Vermès, ”The Jesus Notice of Josephus Re-Examined,” Journal of Jewish Studies 38 (1987), s. 2.

- ^ Avvikelserna består av varianter i uttryck hos kyrkofäder antingen när de citerade stycket eller, som ofta, parafraserade och sammanfattade det. Det är av den anledningen svårt att veta i vad mån dessa varianter beror på att deras förlaga avvek från den normativa texten eller om de själva tog sig friheter i sin tolkning av texten. I de fall deras versioner uttrycker fientlighet överensstämmer de sällan med varandra. Se James N. B. Carleton Paget, ”Some Observations on Josephus and Christianity”, i Jews, Christians and Jewish Christians in Antiquity (Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2010), s. 209–214.

- ^ James N. B. Carleton Paget, ”Some Observations on Josephus and Christianity”, i Jews, Christians and Jewish Christians in Antiquity (Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2010), s. 213–216.

- ^ De slaviska versionerna räknas då inte med eftersom de egentligen är senare gjorda ombearbetningar med mängder av tillägg (se punkt 9 under ”Argument till stöd för äkthet”).

- ^ Shlomo Pines, An Arabic Version of the Testimonium Flavianum and its Implications (Jerusalem: Israel Academy of Sciences and Humanities, 1971).

- ^ Lawrence I. Conrad, “The Conquest of Arwad: A Source-Critical Study in the Historiography of the Early Medieval Near East,” i The Byzantine and Early Islamic Near East: Problems in the Literary Source Material (ed. Averil Cameron and Lawrence I. Conrad; vol. 1 of The Byzantine and Early Islamic Near East; Studies in Late Antiquity and Early Islam 1; Princeton: Darwin Press, 1992), s. 317-401 (322–38).

- ^ Alice Whealey, ”The Testimonium Flavianum in Syriac and Arabic”, New Testament Studies 54.4 (2008), s. 573–590.

- ^ Fernando Bermejo-Rubio, “Was the Hypothetical Vorlage of the Testimonium Flavianum a “Neutral” Text? Challenging the Common Wisdom on Antiquitates Judaicae 18.63-64,” Journal for the Study of Judaism, Volume 45 (2014), s. 326–365 (341).

- ^ Ken Olson. ”Agapius’ testimonium, Crosstalk2”.

- ^ Alice Whealey, ”The Testimonium Flavianum in Syriac and Arabic”, New Testament Studies 54.4, 2008, s. 580.

- ^ Både i bokens inledning och i dess slut skriver Hieronymus att han färdigställde verket i kejsar Theodosius fjortonde år, vilket inföll 19 januari år 392 och avslutades 18 januari år 393.

- ^ Rosamond McKitterick, History and memory in the Carolingian world (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004), s. 226.

- ^ Alice Whealey, ”The Testimonium Flavianum in Syriac and Arabic”, New Testament Studies 54.4, 2008, s. 580–581.

- ^ ”Latin and Syriac writers did not read each others’ works in late antiquity. Both, however, had access to Greek works. The only plausible conclusion is that Jerome and some Syriac Christian (probably the seventh century James of Edessa) both had access to a Greek version of the Testimonium containing the passage ‘he was believed to be the Christ’ rather than ‘he was the Christ.’” Alice Whealey. ”The Testimonium Flavianum Controversy from Antiquity to the Present, s. 10, n. 8.”. Se också Alice Whealey, ”Josephus, Eusebius of Caesarea, and the Testimonium Flavianum”, s. 90, i Böttrich & Herzer, Eds., Josephus und das Neue Testament (Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2007); och ”The Testimonium Flavianum in Syriac and Arabic”, New Testament Studies 54.4 (2008), s. 580–581.

- ^ Robert Eisler, Iesous Basileus ou Basileusas, vol 1 (Heidelberg: Winter, 1929), s. 68.

- ^ Richard Carrier, ”Origen, Eusebius, and the Accidental Interpolation in Josephus, Jewish Antiquities 20.200”, Journal of Early Christian Studies (Vol. 20, No. 4, Winter 2012), s. 493–494.

- ^ Marian Hillar, ”Flavius Josephus and His Testimony Concerning the Historical Jesus,” Essays in the Philosophy of Humanism Vol. 13, Houston, TX., 2005, s. 66–103. Se ”Flavius Josephus and His Testimony Concerning the Historical Jesus, s. 16, 22.”.

- ^ John P. Meier, A Marginal Jew: Rethinking the Historical Jesus, Vol 1: The Roots of the Problem (New York: Doubleday, 1991), s. 60.

- ^ Richard Carrier, ”Origen, Eusebius, and the Accidental Interpolation in Josephus, Jewish Antiquities 20.200”, Journal of Early Christian Studies (Vol. 20, No. 4, Winter 2012), s. 493–494.

- ^ Till stöd för detta antagande finns tre syriska handskrifter. (MS B) från 500-talet och (MS A) från år 462 innehåller båda Eusebios Kyrkohistoria där också Testimonium Flavianum finns översatt till syriska (se Alice Whealey, ”The Testimonium Flavianum in Syriac and Arabic”, New Testament Studies 54.4, 2008, s. 584). Den äldsta syriska handskriften med Testimonium Flavianum i Eusebios Theofania är så gammal som från år 411. (William Hatch, An album of dated Syriac manuscripts, Boston, 1946, s. 52–54.) På grund av de många avskriftsfelen dessa handskrifter innehåller tros de vara flera avskrifter från originalöversättningarna. Ett sådant syriskt original antas ha legat till grund för den översättning till armeniska av Eusebios Kyrkohistoria som gjordes i början av 400-talet. Såväl de syriska handskrifterna som den armeniska texten (”∙Քրիստոս իսկ է նա.”) har han ”var” Messias

- ^ James N. B. Carleton Paget, ”Some Observations on Josephus and Christianity”, i Jews, Christians and Jewish Christians in Antiquity (Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2010), s. 216.

- ^ James N. B. Carleton Paget, ”Some Observations on Josephus and Christianity”, i Jews, Christians and Jewish Christians in Antiquity (Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2010), s. 209.

- ^ Paul L. Maier, Josephus, the Essential Works: A Condensation of “Jewish Antiquities” and “the Jewish War”, transl. and ed, Paul L. Maier (Grand Rapids, MI: Kregel Publications, 1994), s. 284.

- ^ Robert E. Van Voorst, Jesus Outside the New Testament: An Introduction to the Ancient Evidence (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2000), s. 88.

- ^ John P. Meier, A Marginal Jew: Rethinking the Historical Jesus, Vol 1: The Roots of the Problem (New York: Doubleday, 1991), s. 62.

- ^ Louis H. Feldman, “On the Authenticity of the Testimonium Flavianum Attributed to Josephus,” i New Perspectives on Jewish Christian Relations, ed. E. Carlebach & J. J. Schechter (Leiden: Brill, 2012), s. 20.

- ^ De bevarade grekiska handskrifterna innehållande Testimonium Flavianum är A Milan, Codex Ambrosianus (Mediolanensis) F. 128 superior (1000-talet); M Florens, Codex Medicaeus bibl. Laurentianae plut. 69, cod. 10 (1400-talet); W Rom, Codex Vaticanus Graecus 984 (år 1354). Dessa tre handskrifter, A, M och W, tillhör samma familj av handskrifter. (Roger Pearse. ”Josephus: the Main Manuscripts of ”Antiquities””.)

- ^ George A. Wells, The Jesus Legend (Chicago: Open Court, 1996), s. 51.

- ^ J. Neville Birdsall, ”The Continuing Enigma of Josephus’ Testimony about Jesus,” Bulletin of the John Rylands Library of Manchester 67 (1984-85), s. 610.

- ^ Se exempelvis Alice Whealey, ”Josephus, Eusebius of Caesarea, and the Testimonium Flavianum”, s. 90, i Böttrich & Herzer, Eds., Josephus und das Neue Testament (Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2007), framför allt s. 104.

- ^ Géza Vermès, ”The Jesus Notice of Josephus Re-Examined,” Journal of Jewish Studies 38 (1987), s. 1–10.

- ^ Steve Mason, Josephus and the New Testament (Peabody: Massachusetts, 1992), s. 171; (2d ed.; Peabody: Hendrickson, 2003), s. 233.

- ^ John P. Meier, A Marginal Jew: Rethinking the Historical Jesus, Vol 1: The Roots of the Problem (New York: Doubleday, 1991), s. 62–63.

- ^ Josefus Flavius, Judiska fornminnen 8:53, 10:237.

- ^ Josefus Flavius, Judiska fornminnen 9:182, 12:63.

- ^ “In brief, there seems to be no stylistic or historical argument that might be marshalled against the authenticity of the two phrases in question.” Géza Vermès, ”The Jesus Notice of Josephus Re-Examined,” Journal of Jewish Studies 38 (1987), s. 4.

- ^ Paula Fredriksen, Jesus of Nazareth, King of the Jews: A Jewish Life and the Emergence of Christianity (New York: Vintage Books, 2000), s. 248.

- ^ Craig A. Evans, “The Misplaced Jesus: Interpreting Jesus in a Judaic Context”, i Bruce D. Chilton, Craig A. Evans & Jacob Neusner (eds), The Missing Jesus: Rabbinic Judaism and the New Testament: New Research Examining the Historical Jesus in the Context of Judaism (Leiden & Boston: Brill, 2002), s. 21.

- ^ Steve Mason, Josephus and the New Testament (Peabody: Massachusetts, 1992), s. 169–170; (2d ed.; Peabody: Hendrickson, 2003), s. 231.

- ^ Ken Olson, ”A Eusebian Reading of the Testimonium Flavianum” i Eusebius of Caesarea: Tradition and Innovations, ed. A. Johnson & J. Schott (Harvard University Press, 2013), s. 100.

- ^ J. Neville Birdsall, ”The Continuing Enigma of Josephus’s Testimony about Jesus,” Bulletin of the John Rylands University of Manchester 67 (1984-85), s. 621.

- ^ ”J’accorde que le style de Josèphe est adroitement imité, ce qui n’était peut-être pas très difficile …” Charles Guignebert, Jésus, Bibliothèque de Synthèse Historique: L’évolution de L’humanité, Henri Berr (ed.), vol.29 (Paris: La Renaissance du Livre, 1933), s. 19.

- ^ James N. B. Carleton Paget, ”Some Observations on Josephus and Christianity”, i Jews, Christians and Jewish Christians in Antiquity (Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2010), s. 221.

- ^ Robert E. Van Voorst, Jesus Outside the New Testament: An Introduction to the Ancient Evidence (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2000), s. 89–90.

- ^ Ken Olson, ”A Eusebian Reading of the Testimonium Flavianum” i Eusebius of Caesarea: Tradition and Innovations, ed. A. Johnson & J. Schott (Harvard University Press, 2013), s. 105–108.

- ^ Också Feldman noterar att detta stämmer med Eusebios föreställning att det var förutbestämt att Jesu budskap skulle nå alla folk och att hans underverk skulle vinna dem över till den kristna läran. Se Louis H. Feldman, “On the Authenticity of the Testimonium Flavianum Attributed to Josephus,” i New Perspectives on Jewish Christian Relations, ed. E. Carlebach & J. J. Schechter (Leiden: Brill, 2012), s. 22.

- ^ Louis H. Feldman, “On the Authenticity of the Testimonium Flavianum Attributed to Josephus,” i New Perspectives on Jewish Christian Relations, ed. E. Carlebach & J. J. Schechter (Leiden: Brill, 2012), s. 25.

- ^ Ken Olson. ””The Testimonium Flavianum, Eusebius, and Consensus””.

- ^ Josefus Flavius, Judiska fornminnen 8:53, 10:237; Géza Vermès, Jesus in His Jewish Context (London: SCM Press, 2003), s. 92.

- ^ Earl Doherty, Jesus: Neither God Nor Man – The Case for a Mythical Jesus (Ottawa: Age of Reason Publications, 2009), s. 535.

- ^ John P. Meier, A Marginal Jew: Rethinking the Historical Jesus, Vol 1: The Roots of the Problem (New York: Doubleday, 1991), s. 62.

- ^ Craig A. Evans, Jesus and His Contemporaries: Comparative Studies (New York: Brill, 1995), s. 44.

- ^ James D. G. Dunn, Jesus Remembered: Christianity in the Making, Vol. 1 (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2003), s. 141.

- ^ Craig A. Evans, Jesus in non-Christian sources, s. 469; i B. D. Chilton & C. A. Evans (eds), “Studying the Historical Jesus: Evaluations of the State of Current Research” (New Testament Tools and Studies 19; Leiden: Brill 1994).

- ^ Ian Wilson, Jesus: The Evidence (San Francisco: Harper and Row, 1984), s. 60–61

- ^ Origenes, Om Matteus 10:17, Mot Kelsos 1:47 & 2:13.

- ^ Géza Vermès, Jesus in the Jewish World (London: SMC Press, 2010), s. 39–40.

- ^ Tessa Rajak, Josephus, the Historian and His Society, 2. ed. (London: Gerald Duckworth, 2003), 1. ed. 1983, s. 131.

- ^ Ken A. Olson, ”Eusebius and the Testimonium Flavianum,” Catholic Biblical Quarterly 61 (1999), s. 314.

- ^ Paget påpekar att vi inte ska utesluta möjligheten av en kristen glossa: se James N. B. Carleton Paget, ”Some Observations on Josephus and Christianity”, i Jews, Christians and Jewish Christians in Antiquity (Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2010), s. 197, n. 46.

- ^ Richard Carrier, ”Origen, Eusebius, and the Accidental Interpolation in Josephus, Jewish Antiquities 20.200”, Journal of Early Christian Studies (Vol. 20, No. 4, Winter 2012), s. 489–514.

- ^ Ken A. Olson, ”Eusebius and the Testimonium Flavianum,” Catholic Biblical Quarterly 61 (1999), s. 314–315.

- ^ Richard Carrier, ”Origen, Eusebius, and the Accidental Interpolation in Josephus, Jewish Antiquities 20.200”, Journal of Early Christian Studies (Vol. 20, No. 4, Winter 2012), s. 496.

- ^ Origenes, Om Matteus 10:17, Mot Kelsos 1:47.

- ^ Géza Vermès, ”The Jesus Notice of Josephus Re-Examined,” Journal of Jewish Studies 38 (1987), s. 2.

- ^ Louis H. Feldman, “On the Authenticity of the Testimonium Flavianum Attributed to Josephus,” i New Perspectives on Jewish Christian Relations, ed. E. Carlebach & J. J. Schechter (Leiden: Brill, 2012), s. 15–16.

- ^ Shlomo Pines, An Arabic Version of the Testimonium Flavianum and its Implications (Jerusalem: Israel Academy of Sciences and Humanities, 1971), s. 66.

- ^ Se också James N. B. Carleton Paget, ”Some Observations on Josephus and Christianity”, i Jews, Christians and Jewish Christians in Antiquity (Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2010), s. 205–206.

- ^ S. G. F. Brandon, Jesus and the Zealots: A Study of the Political Factor in Primitive Christianity (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1967), s. 361.

- ^ Richard Carrier, On the Historicity of Jesus: Why We Might Have Reason for Doubt (Sheffield Phoenix Press, 2014), s. 335.

- ^ Robert M. Price, The Case Against the Case for Christ: A New Testament Scholar Refutes Lee Strobel (Cranford, NJ: American Atheist Press, 2010), s. 86.

- ^ Origenes, Mot Kelsos 1:28, 1:47. Kelsos numera försvunna verk hette ”Sanningens ord” (grekiska: Logos Alêthês) och skrevs ca år 180.

- ^ James N. B. Carleton Paget, ”Some Observations on Josephus and Christianity”, i Jews, Christians and Jewish Christians in Antiquity (Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2010), s. 203.

- ^ Richard Carrier, ”Origen, Eusebius, and the Accidental Interpolation in Josephus, Jewish Antiquities 20.200”, Journal of Early Christian Studies (Vol. 20, No. 4, Winter 2012), s. 492.

- ^ Josefus, Judiska fornminnen 18:116–119.

- ^ Origenes, Mot Kelsos 1:47.

- ^ J. Neville Birdsall, ”The Continuing Enigma of Josephus’s Testimony about Jesus,” Bulletin of the John Rylands University of Manchester 67 (1984-85), s. 618.

- ^ Origenes, Om Matteus 10:17, Mot Kelsos 1:47 & 2:13.

- ^ Richard Carrier, ”Origen, Eusebius, and the Accidental Interpolation in Josephus, Jewish Antiquities 20.200”, Journal of Early Christian Studies (Vol. 20, No. 4, Winter 2012), s. 499–503.

- ^ Ken A. Olson, ”Eusebius and the Testimonium Flavianum,” Catholic Biblical Quarterly 61 (1999), s. 317–318.

- ^ Alice Whealey, ”Josephus, Eusebius of Caesarea, and the Testimonium Flavianum”, s. 90, i Böttrich & Herzer, Eds., Josephus und das Neue Testament (Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2007).

- ^ Ken A. Olson, ”Eusebius and the Testimonium Flavianum,” Catholic Biblical Quarterly 61 (1999), s. 317–318.

- ^ Richard Carrier, ”Origen, Eusebius, and the Accidental Interpolation in Josephus, Jewish Antiquities 20.200”, Journal of Early Christian Studies (Vol. 20, No. 4, Winter 2012), s. 507–511, 514.

- ^ Elledge påpekar att Origenes säger att Jesus inte erkände Jesus som Messias i ett sammanhang där han synbarligen behandlar Jakobpassagen. Casey D. Elledge, Josephus, Tacitus and Suetonius: Seeing Jesus through the Eyes of Classical Historians, s. 696–697, i Jesus Research: New Methodologies and Perceptions: The Second Princeton- Prague Symposium on Jesus Research, Princeton 2007, ed. James H. Charlesworth.

- ^ James N. B. Carleton Paget, ”Some Observations on Josephus and Christianity”, i Jews, Christians and Jewish Christians in Antiquity (Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2010), s. 203–204.

- ^ J. Neville Birdsall, ”The Continuing Enigma of Josephus’s Testimony about Jesus,” Bulletin of the John Rylands University of Manchester 67 (1984-85), s. 618.

- ^ Ian Wilson, Jesus: The Evidence (San Francisco: Harper and Row, 1984), s. 61–62

- ^ Se Shlomo Pines, An Arabic Version of the Testimonium Flavianum and its Implications (Jerusalem: Israel Academy of Sciences and Humanities, 1971).

- ^ Robert E. Van Voorst, Jesus Outside the New Testament: An Introduction to the Ancient Evidence (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2000), s. 97–98.

- ^ Alice Whealey, ”The Testimonium Flavianum in Syriac and Arabic”, New Testament Studies 54.4 (2008), s. 573–590.

- ^ Ken Olson. ”Agapius’ testimonium, Crosstalk2”.

- ^ Se Alice Whealey, ”The Testimonium Flavianum in Syriac and Arabic”, New Testament Studies 54.4, 2008, s. 573–590.

- ^ I medeltida handskrifter bär verket namnet De excidio urbis Hierosolymitanae (Om staden Jerusalems ödeläggelse). Namnet Pseudo-Hegesippos kommer av att verket felaktigt antagits vara skrivet av den kristne grekiske författaren Hegesippos som levde ca 110–ca 180 vt.

- ^ Pseudo-Hegesippos, De excidio Hierosolymitano 2:12.

- ^ Albert A. Bell JR, ”Josephus and Pseudo-Hegesippus”; i Louis H. Feldman, Gōhei Hata, Josephus, Judaism and Christianity (Detroit 1987), s. 350.

- ^ Alice Whealey, Josephus on Jesus, The Testimonium Flavianum Controversy from Late Antiquity to Modern Times, Studies in Biblical Literature 36 (New York: Peter Lang, 2003), s. 31–33.

- ^ James N. B. Carleton Paget, ”Some Observations on Josephus and Christianity”, Journal of Theological Studies 52:2 (2001), s. 567.

- ^ James N. B. Carleton Paget, ”Some Observations on Josephus and Christianity”, Journal of Theological Studies 52:2 (2001), s. 566–567.

- ^ Alice Whealey, ”Josephus, Eusebius of Caesarea, and the Testimonium Flavianum”, s. 79, n. 16, i Böttrich & Herzer, Eds., Josephus und das Neue Testament (Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2007).

- ^ Emil Schürer, The History of the Jewish People in the Age of Jesus Christ: 175 B.C.–A.D. 135, Volume I (Edinburgh 1973), s. 58.

- ^ Marian Hillar, ”Flavius Josephus and His Testimony Concerning the Historical Jesus,” Essays in the Philosophy of Humanism Vol. 13, Houston, TX., 2005, s. 66–103. Se ”Flavius Josephus and His Testimony Concerning the Historical Jesus, s. 17.”.

- ^ Latinets deum fatebantur kan också översättas till ”erkände att han var Gud” som Alice Whealey gör: ”acknowledged him to be God”; Alice Whealey, Josephus on Jesus, The Testimonium Flavianum Controversy from Late Antiquity to Modern Times, Studies in Biblical Literature 36 (New York: Peter Lang, 2003), s. 32–33. Heinz Schreckenberg översätter det emellertid till ”erkände hans gudomlighet”: ”confessed his divinity”. Heinz Schreckenberg, Kurt Schubert (eds.), Jewish Historiography and Iconography in Early and Medieval Christianity, Assen and Maastricht 1992, s. 72.

- ^ Ken Olson. ”Pseudo-Hegesippus’ Testimonium, Crosstalk2”.

- ^ Marian Hillar, ”Flavius Josephus and His Testimony Concerning the Historical Jesus,” Essays in the Philosophy of Humanism Vol. 13, Houston, TX., 2005, s. 66–103. Se ”Flavius Josephus and His Testimony Concerning the Historical Jesus, s. 18”.

- ^ John P. Meier, A Marginal Jew: Rethinking the Historical Jesus, Vol 1: The Roots of the Problem (New York: Doubleday, 1991), s. 61–62.

- ^ Géza Vermès, Jesus in the Jewish World (London: SMC Press, 2010), s. 41–44.

- ^ James Charlesworth, Jesus within Judaism: New Light from Exciting Archaeological Discoveries (New York: Doubleday, 1988), s. 93.

- ^ Robert E. Van Voorst, Jesus Outside the New Testament: An Introduction to the Ancient Evidence (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2000), s. 96.

- ^ Earl Doherty, Jesus: Neither God Nor Man – The Case for a Mythical Jesus (Ottawa: Age of Reason Publications, 2009), s. 539–540.

- ^ Ken Olson, ”A Eusebian Reading of the Testimonium Flavianum” i Eusebius of Caesarea: Tradition and Innovations, ed. A. Johnson & J. Schott (Harvard University Press, 2013), s. 100.

- ^ Marian Hillar, ”Flavius Josephus and His Testimony Concerning the Historical Jesus,” Essays in the Philosophy of Humanism Vol. 13, Houston, TX., 2005, s. 66–103. Se ”Flavius Josephus and His Testimony Concerning the Historical Jesus, s. 24.”.

- ^ De 30 bevarade handskrifterna är alla från perioden 1400-talet till 1700-talet – den äldsta är daterad till år 1463.

- ^ Roger Pearse (2002). ”Notes on the Old Slavonic Josephus”.

- ^ Instoppen om Jesus förekommer på motsvarande ställen i Om det judiska kriget 2:9:3 (eller 2:174), 5:5:2, 5:5:4 och 6:5:4).

- ^ Solomon Zeitlin, ”The Hoax of the ’Slavonic Josephus’”, The Jewish Quarterly Review, New Series (Vol. 39, No. 2, Oct., 1948), s. 177.

- ^ Robert Eisler, The Messiah Jesus and John the Baptist: According to Flavius Josephus’ recently rediscovered ‘Capture of Jerusalem’ and the other Jewish and Christian sources (London: Methuen, 1931).

- ^ Étienne Nodet, The Emphasis on Jesus’ Humanity in the Kerygma , s. 739, i James H. Charlesworth, Jesus Research: New Methodologies and Perceptions, Princeton-Prague Symposium 2007 (Grand Rapids, Eerdmans, 2014).

- ^ John P. Meier, A Marginal Jew: Rethinking the Historical Jesus, Vol 1: The Roots of the Problem (New York: Doubleday, 1991), s. 57.

- ^ Alice Whealey. ”The Testimonium Flavianum Controversy from Antiquity to the Present, s. 7–8.”.

- ^ ”It is doubtful whether any scholars today would defend the hypothesis … that the Old Russian adaptation of Jewish War contains any material deriving directly from Josephus.” Alice Whealey, Josephus on Jesus, The Testimonium Flavianum Controversy from Late Antiquity to Modern Times, Studies in Biblical Literature 36 (New York: Peter Lang, 2003), s. 195.

- ^ Robert E. Van Voorst, Jesus Outside the New Testament: An Introduction to the Ancient Evidence (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2000), s. 87–88.

- ^ Steve Mason, Josephus and the New Testament (Peabody: Massachusetts, 1992), s. 169–170; (2d ed.; Peabody: Hendrickson, 2003), s. 231.

- ^ Ken Olson, ”A Eusebian Reading of the Testimonium Flavianum” i Eusebius of Caesarea: Tradition and Innovations, ed. A. Johnson & J. Schott (Harvard University Press, 2013), s. 103; Alice Whealey, ”Josephus, Eusebius of Caesarea, and the Testimonium Flavianum”, s. 80, i Böttrich & Herzer, Eds., Josephus und das Neue Testament (Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2007).

- ^ Ken Olson, ”A Eusebian Reading of the Testimonium Flavianum” i Eusebius of Caesarea: Tradition and Innovations, ed. A. Johnson & J. Schott (Harvard University Press, 2013), s. 110, n. 44.

- ^ Alice Whealey, ”Josephus, Eusebius of Caesarea, and the Testimonium Flavianum”, s. 77, 101–105, i Böttrich & Herzer, Eds., Josephus und das Neue Testament (Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2007).

- ^ John P. Meier, A Marginal Jew: Rethinking the Historical Jesus, Vol 1: The Roots of the Problem (New York: Doubleday, 1991), s. 81, n. 41.

- ^ Judas från Galileen, Theudas, egyptern, en icke namngiven profet och Menahem.

- ^ Jona Lendering. ”Overview of articles on ‘Messiah’”.

- ^ John Dominic Crossan, The Historical Jesus: the life of a Mediterranean Jewish peasant (San Francisco: Harper 1991), s. 199.

- ^ Andreas J. Köstenberger, L. Scott Kellum, Charles L. Quarles, The Cradle, the Cross, and the Crown: An Introduction to the New Testament (Nashville: Broadman & Holman Academic, 2009), s. 105.

- ^ Josefus, Om det judiska kriget 6.312–313.

- ^ Alice Whealey, ”The Testimonium Flavianum in Syriac and Arabic”, New Testament Studies 54.4, 2008, s. 575.

- ^ Giorgio Jossa, “Jews, Romans, and Christians: from the Bellum Judaicum to the Antiquitates”, s. 333; i Sievers & Lembi (eds.), Josephus and Jewish history in Flavian Rome and Beyond (Leiden: E. J. Brill, 2005).

- ^ G. R. S. Mead, Gnostic John the Baptizer: Selections from the Mandaean John-Book, 1924, III The Slavonic Josephus’ Account of the Baptist and Jesus, s. 98.

- ^ Earl Doherty, Jesus: Neither God Nor Man – The Case for a Mythical Jesus (Ottawa: Age of Reason Publications, 2009), s. 548–549.

- ^ Robert Grant, A Historical Introduction to the New Testament (New York: Harper & Row, 1963).

- ^ Giorgio Jossa, “Jews, Romans, and Christians: from the Bellum Judaicum to the Antiquitates”, s. 331–342; i Sievers & Lembi (eds.), Josephus and Jewish history in Flavian Rome and Beyond (Leiden: E. J. Brill, 2005).

- ^ Earl J. Doherty, The Jesus Puzzle: Did Christianity Begin with a Mythical Christ? (Ottawa: Canadian Humanist Publications), 1999, s. 222.

- ^ Josefus, Judiska fornminnen 18:116–119.

- ^ Josefus, Judiska fornminnen 18:65–80.

- ^ Richard Carrier, ”Origen, Eusebius, and the Accidental Interpolation in Josephus, Jewish Antiquities 20.200”, Journal of Early Christian Studies (Vol. 20, No. 4, Winter 2012), s. 490.

- ^ Richard Carrier, On the Historicity of Jesus: Why We Might Have Reason for Doubt (Sheffield Phoenix Press, 2014), s. 337.

- ^ E. P. Sanders, The Historical Figure of Jesus (New York: Penguin Press, 1993), s. 50–51.

- ^ James N. B. Carleton Paget, ”Some Observations on Josephus and Christianity”, Journal of Theological Studies 52:2 (2001), s. 579.

- ^ Eduard Norden, ”Josephus und Tacitus über Jesus Christus und eine messianische Prophetie”, i Kleine Schriften zum klassischen Altertum (Berlin 1966), s. 245–250.

- ^ Steve Mason, Josephus and the New Testament (Peabody: Massachusetts, 1992), s. 164–165; (2d ed.; Peabody: Hendrickson, 2003), s. 225–227.

- ^ George A. Wells, The Jesus Legend (Chicago: Open Court, 1996), s. 50–51.

- ^ Marian Hillar, ”Flavius Josephus and His Testimony Concerning the Historical Jesus,” Essays in the Philosophy of Humanism Vol. 13, Houston, TX., 2005, s. 66–103. Se ”Flavius Josephus and His Testimony Concerning the Historical Jesus, s. 4.”.

- ^ Steve Mason, Josephus and the New Testament (Peabody: Massachusetts, 1992), s. 166–167; (2d ed.; Peabody: Hendrickson, 2003), s. 227–228.

- ^ Josefus, Liv 2.

- ^ Leo Wohleb hänvisar till Judiska fornminnen 8.26ff, 10:24ff och 13:171ff, passager som alla avbryter den pågående berättelsen. Leo Wohleb, ”Das Testimonium Flavianum. Ein kritischer Bericht über den Stand der Frage”, Römische Quartalschrift 35 (1927), s. 151–169.

- ^ John P. Meier, A Marginal Jew: Rethinking the Historical Jesus, Vol 1: The Roots of the Problem (New York: Doubleday, 1991), s. 86.

- ^ Frank R. Zindler, The Jesus the Jews Never Knew: Sepher Toldoth Yeshu and the Quest of the Historical Jesus in Jewish Sources (New Jersey: American Atheist Press, 2003), s. 42–43.

- ^ Eduard Norden, ”Josephus und Tacitus über Jesus Christus und eine messianische Prophetie”, i Kleine Schriften zum klassischen Altertum (Berlin 1966), s. 241–275.

- ^ James N. B. Carleton Paget, ”Some Observations on Josephus and Christianity”, i Jews, Christians and Jewish Christians in Antiquity (Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2010), s. 225–226.

- ^ Steve Mason, Josephus and the New Testament (Peabody: Massachusetts, 1992), s. 165; (2d ed.; Peabody: Hendrickson, 2003), s. 226–227.

- ^ Josefus, Judiska fornminnen 18:60–62.

- ^ Richard Carrier, ”Origen, Eusebius, and the Accidental Interpolation in Josephus, Jewish Antiquities 20.200”, Journal of Early Christian Studies (Vol. 20, No. 4, Winter 2012), s. 489–490.

- ^ Richard Carrier, On the Historicity of Jesus: Why We Might Have Reason for Doubt (Sheffield Phoenix Press, 2014), s. 337.

- ^ John P. Meier, A Marginal Jew: Rethinking the Historical Jesus, Vol 1: The Roots of the Problem (New York: Doubleday, 1991), s. 86.

- ^ C. Martin, ”Le Testimonium Flavianum. Vers une solution definitive?”, Revue Beige de Philologie et d’Histoire 20 (1941), s. 422–431.

- ^ Gerd Theißen & Annette Merz, The Historical Jesus: A Comprehensive Guide (Minneapolis: Fortress, 1998), s. 72.

- ^ Dieter Sänger, “Auf Betreiben der Vornehmsten unseres Volkes,” i Das Urchristentum in seiner literarischen Geschichte: Festschrift für Jürgen Becker zum 65. Geburtstag , Ulrich Mell, Ulrich B. Müller (eds.) (Berlin: De Gruyter, 1999), s. 21.

- ^ Robert Eisler, The Messiah Jesus and John the Baptist: According to Flavius Josephus’ recently rediscovered ‘Capture of Jerusalem’ and the other Jewish and Christian sources, 1931, s. 62.

- ^ David W. Chapman, Ancient Jewish and Christian Perceptions of Crucifixion; Wissenschaftliche Untersuchungen zum Neuen Testament; II ser. 244 (Tubingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2008), s. 80.

- ^ 1) Pseudo-Justinus, 2) Theofilos av Antiochia, 3) Melito av Sardes, 4) Minucius Felix, 5) Irenaeus, 6) Klemens av Alexandria, 7) Julius Africanus, 8) Tertullianus, 9) Hippolytos, 10) Origenes, 11) Methodios av Olympos, 12) Lactantius.(Michael Hardwick, Josephus as an Historical Source in Patristic Literature through Eusebios; Heinz Schreckenberg, Die Flavius-Josephus-Tradition in Antike und Mittelalter, 1972, s. 70ff). Till dessa kan också 13) Cyprianus av Karthago och 14) den grekisk-kristne apologeten Arnobius den äldre fogas. (Earl Doherty, Jesus: Neither God Nor Man – The Case for a Mythical Jesus, Ottawa: Age of Reason Publications, 2009, s. 538).

- ^ Justinus Martyren, Dialog med juden Tryfon 8.

- ^ Louis H. Feldman, ”Flavius Josephus Revisited: the Man, His writings, and His Significance”, 1972, s. 822 i Aufstieg und Niedergang der römischen Welt, 21:2 (1984).

- ^ Louis H. Feldman, ”Flavius Josephus Revisited: the Man, His writings, and His Significance”, 1972, s. 823–824 i Aufstieg und Niedergang der römischen Welt, 21:2 (1984).

- ^ Alice Whealey, ”Josephus, Eusebius of Caesarea, and the Testimonium Flavianum”, s. 74–75, i Böttrich & Herzer, Eds., Josephus und das Neue Testament (Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2007).

- ^ Fernando Bermejo-Rubio, “Was the Hypothetical Vorlage of the Testimonium Flavianum a “Neutral” Text? Challenging the Common Wisdom on Antiquitates Judaicae 18.63-64,” Journal for the Study of Judaism, Volume 45 (2014), s. 326–365 (339).

- ^ John P. Meier, A Marginal Jew: Rethinking the Historical Jesus, Vol 1: The Roots of the Problem (New York: Doubleday, 1991), s. 68, 79, 87.

- ^ Se Robert Eisler, The Messiah Jesus and John the Baptist: According to Flavius Josephus’ recently rediscovered ‘Capture of Jerusalem’ and the other Jewish and Christian sources, 1931, och s. 62 för Eislers hypotetiska rekonstruktion av Testimonium Flavianum i vilken Jesus framställs så negativt att Eisler kan tänka sig att Josefus också har skrivit passagen.

- ^ För en nutida artikel som argumenterar för att Josefus ursprungliga version var negativ, se Fernando Bermejo-Rubio, “Was the Hypothetical Vorlage of the Testimonium Flavianum a “Neutral” Text? Challenging the Common Wisdom on Antiquitates Judaicae 18.63-64,” Journal for the Study of Judaism, Volume 45 (2014), s. 326–365.

- ^ De enda texter som går att åberopa är de varianter som förekommer i Slaviska Josefus och dessa avfärdas numera nästan samfällt som medeltida förfalskningar (se punkt 9 under ”Argument till stöd för äkthet”).

- ^ Louis H. Feldman, ”Flavius Josephus Revisited: the Man, His writings, and His Significance”, 1972, s. 822 i Aufstieg und Niedergang der römischen Welt, 21:2 (1984).

- ^ Johannes Chrysostomos, Predikan 76 om Matteus.

- ^ Fotios, Bibliotheke 47 (om Om det judiska kriget) och 76 & 238 (om Judiska fornminnen).

- ^ Fotios, Bibliotheke 238.

- ^ Exempelvis beklagar sig Fotios över att Justus av Tiberias i (det numera försvunna verket) Palestinsk historia “uppvisar judarnas vanliga fel” och inte ens nämner Kristus, hans liv och hans mirakler; Fotios, Bibliotheke 33.

- ^ Louis H. Feldman, ”Flavius Josephus Revisited: the Man, His writings, and His Significance”, 1972, s. 823 i Aufstieg und Niedergang der römischen Welt, 21:2 (1984).

- ^ Joseph Sievers, “The ancient lists of contents of Josephus’ Antiquities”, s. 271–292 i Studies in Josephus and the Varieties of Ancient Judaism: Louis H. Feldman Jubilee Volume, eds. S. J. D. Cohen & J. J. Schwartz (Leiden; Boston: Brill, 2007).

- ^ Louis H. Feldman, ”Introduction”; i Louis H. Feldman, Gōhei Hata, Josephus, Judaism and Christianity (Detroit 1987), s. 57.

- ^ James N. B. Carleton Paget, ”Some Observations on Josephus and Christianity”, Journal of Theological Studies 52:2 (2001), s. 556–557.

- ^ Louis H. Feldman, “On the Authenticity of the Testimonium Flavianum Attributed to Josephus,” i New Perspectives on Jewish Christian Relations, ed. E. Carlebach & J. J. Schechter (Leiden: Brill, 2012), s. 19–20.

- ^ Ken Olson, ”A Eusebian Reading of the Testimonium Flavianum” i Eusebius of Caesarea: Tradition and Innovations, ed. A. Johnson & J. Schott (Harvard University Press, 2013), s. 102–108.

- ^ Detta är John P. Meiers huvudsakliga ståndpunkt i hans inflytelserika bok A Marginal Jew: Rethinking the Historical Jesus, Vol 1: The Roots of the Problem (New York: Doubleday, 1991), s. 56–88.

- ^ I detta avseende går kanske Vincent längst genom att omtolka i stort sett alla problematiska passager i Testimonium Flavianum så att de ska ses som ironiska och egentligen negativa. A. Vincent Cernuda, “El testimonio Flaviano. Alarde de solapada ironia”, ”Estudios Biblicos” 55 (1997), s. 355–385 & 479–508. Se James N. B. Carleton Paget, ”Some Observations on Josephus and Christianity”, i Jews, Christians and Jewish Christians in Antiquity (Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2010), s. 229–233.

- ^ Bland dem som på senare år argumenterat längs dessa banor märks Alice A. Whealey, Josephus on Jesus, The Testimonium Flavianum Controversy from Late Antiquity to Modern Times, Studies in Biblical Literature 36 (New York: Peter Lang, 2003); ”Josephus, Eusebius of Caesarea, and the Testimonium Flavianum”, s. 73–116 (78), i Böttrich & Herzer, Eds., Josephus und das Neue Testament (Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2007) och Serge Bardet, Le Testimonium flavianum, Examen historique, considérations historiographiques, Josèphe et son temps 5 (Paris: Cerf, 2002), s. 79–85.

- ^ Sammanfattat av Ken Olson i ”A Eusebian Reading of the Testimonium Flavianum” i Eusebius of Caesarea: Tradition and Innovations, ed. A. Johnson & J. Schott (Harvard University Press, 2013), s. 99.

- ^ Detta är precis vad Ken Olson demonstrerar med Apg 2:22–24 i ”Eusebius and the Testimonium Flavianum,” Catholic Biblical Quarterly 61 (1999), s. 308–309.

- ^ James N. B. Carleton Paget, ”Some Observations on Josephus and Christianity”, i Jews, Christians and Jewish Christians in Antiquity (Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2010), s. 236–237.

- ^ Solomon Zeitlin, “The Christ Passage in Josephus”, The Jewish Quarterly Review, New Series, Volume XVIII, 1928, s. 231–255.

- ^ Ken Olson, ”A Eusebian Reading of the Testimonium Flavianum” i Eusebius of Caesarea: Tradition and Innovations, ed. A. Johnson & J. Schott (Harvard University Press, 2013), s. 97–114.

- ^ Ken A. Olson, ”Eusebius and the Testimonium Flavianum,” Catholic Biblical Quarterly 61 (1999), s. 305–322.

- ^ Eusebios, Demonstratio Evangelica 3:5:105f. Ken A. Olson, ”Eusebius and the Testimonium Flavianum,” Catholic Biblical Quarterly 61 (1999), s. 309.

- ^ James N. B. Carleton Paget, ”Some Observations on Josephus and Christianity”, i Jews, Christians and Jewish Christians in Antiquity (Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2010), s. 203.

- ^ James N. B. Carleton Paget, ”Some Observations on Josephus and Christianity”, Journal of Theological Studies 52:2 (2001), s. 539–624.

- ^ Alice Whealey, ”Josephus, Eusebius of Caesarea, and the Testimonium Flavianum”, s. 73–116, i Böttrich & Herzer, Eds., Josephus und das Neue Testament (Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2007).

- ^ Alice Whealey, ”Josephus, Eusebius of Caesarea, and the Testimonium Flavianum”, s. 83, i Böttrich & Herzer, Eds., Josephus und das Neue Testament (Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2007).

- ^ Ken Olson, ”A Eusebian Reading of the Testimonium Flavianum” i Eusebius of Caesarea: Tradition and Innovations, ed. A. Johnson & J. Schott (Harvard University Press, 2013), s. 111.

- ^ Eusebios, Kyrkohistoria 1.2.23; Demonstratio Evangelica 114–115, 123, & 125.

- ^ Eusebios, Kyrkohistoria 1.11.8 (Testimonium Flavianum) & 2.1.7; Eclogae Propheticae, s. 168, rad 15.

- ^ Eusebios, Kyrkohistoria 3.3.2, 3.3.3.

- ^ “In total, then, three phrases—‘who wrought surprising feats,’ ‘tribe of the Christians,’ and ‘still to this day’—are found elsewhere in Eusebius and in no other author.” Louis H. Feldman, “On the Authenticity of the Testimonium Flavianum Attributed to Josephus,” i New Perspectives on Jewish Christian Relations, ed. E. Carlebach & J. J. Schechter (Leiden: Brill, 2012), s. 26.

- ^ “… it must have greatly disturbed him that no one before him, among so many Christian writers, had formulated even a thumbnail sketch of the life and achievements of Jesus. Consequently, he may have been motivated to originate the Testimonium.” Louis H. Feldman, “On the Authenticity of the Testimonium Flavianum Attributed to Josephus,” i New Perspectives on Jewish Christian Relations, ed. E. Carlebach & J. J. Schechter (Leiden: Brill, 2012), s. 27.

- ^ “In conclusion, there is reason to think that a Christian such as Eusebius would have sought to portray Josephus as more favorably disposed toward Jesus and may well have interpolated such a statement as that which is found in the Testimonium Flavianum.” Louis H. Feldman, “On the Authenticity of the Testimonium Flavianum Attributed to Josephus,” i New Perspectives on Jewish Christian Relations, ed. E. Carlebach & J. J. Schechter (Leiden: Brill, 2012), s. 28.

- ^ Gary J. Goldberg, “The Coincidences of the Emmaus Narrative of Luke and the Testimonium of Josephus,” Journal for the Study of the Pseudepigrapha 13 (1995), s. 59–77. Se ”The Coincidences of the Emmaus Narrative of Luke and the Testimonium of Josephus”.

- ^ Karl–Heinz Fleckenstein et al., Emmaus in Judäa, Geschichte-Exegese-Archäologie (Gießen: Brunnen Verlag, 2003), s. 176.

- ^ James N. B. Carleton Paget, ”Some Observations on Josephus and Christianity”, Journal of Theological Studies 52:2 (2001), s. 593–594.

- ^ Gary J. Goldberg, “The Coincidences of the Emmaus Narrative of Luke and the Testimonium of Josephus,” Journal for the Study of the Pseudepigrapha 13 (1995), s. 59–77. Se ”The Coincidences of the Emmaus Narrative of Luke and the Testimonium of Josephus.”.

- ^ Se också James N. B. Carleton Paget, ”Some Observations on Josephus and Christianity”, i Jews, Christians and Jewish Christians in Antiquity (Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2010), s. 237.

- ^ Whealey hävdar att det är vanligt i kristna texter att Jesus sägs ha uppstått efter tre dagar i stället för på den tredje dagen, och att exempelvis de flesta handskrifter av Mark 8:31 har den läsarten; Alice Whealey, ”The Testimonium Flavianum in Syriac and Arabic”, New Testament Studies 54.4 (2008), s. 579, n. 21.

- ^ Josefus, Judiska fornminnen 18:63–64.

- ^ Gary J. Goldberg, “The Coincidences of the Emmaus Narrative of Luke and the Testimonium of Josephus,” Journal for the Study of the Pseudepigrapha 13 (1995), s. 59–77. Se ”The Coincidences of the Emmaus Narrative of Luke and the Testimonium of Josephus.”.

- ^ Richard Carrier, ”Eusebius, and the Accidental Interpolation in Josephus, Jewish Antiquities 20.200”, i Hitler Homer Bible Christ: The Historical Papers of Richard Carrier 1995-2013 (Philosophy Press: Richmond, California, 2014), s. 344.

- ^ Josefus, Judiska fornminnen 18:63–64; 20:200.

- ^ Richard Carrier, ”Origen, Eusebius, and the Accidental Interpolation in Josephus, Jewish Antiquities 20.200”, Journal of Early Christian Studies (Vol. 20, No. 4, Winter 2012), s. 489–514.

- ^ Richard Carrier, On the Historicity of Jesus: Why We Might Have Reason for Doubt (Sheffield Phoenix Press, 2014), s. 333, n. 81.

- ^ Gary J. Goldberg, “The Coincidences of the Emmaus Narrative of Luke and the Testimonium of Josephus,” Journal for the Study of the Pseudepigrapha 13 (1995), s. 59–77. Se ”The Coincidences of the Emmaus Narrative of Luke and the Testimonium of Josephus, s. 1–2”.

- ^ Richard Carrier, On the Historicity of Jesus: Why We Might Have Reason for Doubt (Sheffield Phoenix Press, 2014), s. 333, n. 81.

- ^ Roger Viklund, Jesuspassagerna hos Josefus – en fallstudie, ”Brodern till Jesus som kallades Kristus, vars namn var Jakob”.

- ^ Grekiska originaltexten till Flavius Josephus, Antiquitates Judaicae, 20:197–203 (20.9.1) ”Perseus, Greek (Benedikt Niese, 1892)”.

- ^ Louis H. Feldman, ”Introduction”; i Louis H. Feldman, Gōhei Hata, Josephus, Judaism and Christianity (Detroit 1987), s. 55–57.

- ^ Robert E. Van Voorst, Jesus Outside the New Testament: An Introduction to the Ancient Evidence (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2000), s. 83.

- ^ Richard J. Bauckham, “For What Offense Was James Put to Death?” i James the Just and Christian Origins, ed. Bruce Chilton & Craig A. Evans (Leiden: Brill, 1999), s. 199–231.

- ^ Claudia J. Setzer, Jewish Responses to Early Christians: History and Polemics, 30-150 C.E. (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 1994), s. 108–109.

- ^ Zvi Baras, “The Testimonium Flavianum and the Martyrdom of James”; i Louis H. Feldman, Gōhei Hata, Josephus, Judaism and Christianity (Detroit 1987), s. 341.

- ^ Ken A. Olson, ”Eusebius and the Testimonium Flavianum,” Catholic Biblical Quarterly 61 (1999), s. 314.

- ^ John P. Meier, A Marginal Jew: Rethinking the Historical Jesus, Vol 1: The Roots of the Problem (New York: Doubleday, 1991), s. 57.

- ^ John P. Meier, A Marginal Jew: Rethinking the Historical Jesus, Vol 1: The Roots of the Problem (New York: Doubleday, 1991), s. 57.