Då följer del 2 av min Wikipediaartikel om Testimonium Flavianum. Denna del återger i huvudsak argument till stöd för att hela stycket är en kristen förfalskning, en ståndpunkt som jag alltså delar.

Del 1 av artikeln finns att läsa här: Testimonium Flavianum, del 1

Testimonium Flavianum (del 2)

Innehåll

– – – – – – – – – – – – –

- 5 Argument till stöd för förfalskning i sin helhet

- 5.1 Att Josefus inte skrivit något alls av Testimonium Flavianum

- 5.1.1 1) Språket

- 5.1.2 2) Identifieringen av Jesus som Messias

- 5.1.3 3) Josefus nämner inte Jesus i sitt äldre historieverk

- 5.1.4 4) Testimonium Flavianum är orimligt kort

- 5.1.5 5) Testimonium Flavianum passar ej i sitt sammanhang

- 5.1.6 6) Meningen efter Testimonium Flavianum syftar på stycket före

- 5.1.7 7) Testimonium Flavianum okänt fram till 300-talet

- 5.1.8 8) En handskrift där Testimonium Flavianum saknades

- 5.1.9 9) En innehållsförteckning utan Testimonium Flavianum

- 5.1.10 10) Testimonium Flavianum är en enhet och allt eller inget måste behållas

- 5.1.11 11) Eusebios skapade Testimonium Flavianum

- 5.1 Att Josefus inte skrivit något alls av Testimonium Flavianum

- 6 Goldbergs parallell med Emmausberättelsen

- 7 Referenser

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – –

Argument till stöd för förfalskning i sin helhet

Att Josefus inte skrivit något alls av Testimonium Flavianum

1) Språket

Testimonium Flavianum innehåller flera uttryck som anses främmande för Josefus. Exempelvis använder Josefus aldrig grekiskans poiêtês i betydelsen av någon som ”utför”, en ”skapare”, utan enbart i betydelsen poet,[136] vilket innebär att uttrycket paradoxôn ergôn poiêtês, alltså ”utförde underbara verk”, inte är typiskt för honom.[137] Vidare finns uttrycket ”de kristnas [folk]stam” avseende samfundet av kristna. Ingen enda gång använder Josefus uttrycket ”stam” (grekiska: fylon) för att beteckna en religiös gemenskap, som ju kristna utgjorde. Slutligen förekommer uttrycket eis eti te nun, ”intill nuvarande tidpunkt”, ingen annanstans hos Josefus förutom i Testimonium Flavianum, medan Eusebios använde det vid sex tillfällen.[138]

Emot detta invänder Whealey att texten kan ha blivit korrupt i samband med att nya handskrifter ersatte de gamla. Exempelvis lyder texten i de två äldsta handskrifterna av Judiska fornminnen ”eis te nun” i stället för eis eti te nun, och den läsarten förekommer också på andra ställen. Eftersom Josefus använder uttrycket eis te nun talar detta enligt Whealey för att han skrivit nämnda parti i Testimonium Flavianum.[139] Vidare kan vissa ord och uttryck förvisso förekomma i en annan form eller så endast en gång i en författares hela verk utan att det därmed är misstänkt. Meier menar att det kan vara en ren tillfällighet att Josefus inte använt poiêtês i betydelsen av att göra något eftersom han använder närbesläktade former av ordet i den betydelsen.[140]

2) Identifieringen av Jesus som Messias

Jesus identifieras som Messias vid ett tillfälle direkt och vid ytterligare två tillfällen indirekt, genom att texten antyder att han egentligen var Gud och att profeterna förutsagt hans ankomst. Åtminstone det senare identifierar Jesus som Messias. Det faktum att ordet Messias alls förekommer, oavsett om man tror att Josefus utnämnt Jesus till Messias eller bara redogjort för att andra ansåg honom vara Messias, talar emot att Josefus skrivit Testimonium Flavianum. Josefus beskriver åtminstone femton möjliga Messiasgestalter (Testimonium Flavianum borträknat) där fem relativt säkert såg sig själva som Messias eller av folket betraktades som Messias.[141] Men Josefus uttrycker bara förakt för dessa fem Messiasgestalter[142] och undviker att använda ordet Messias om någon av dem.[143] Ordet Messias (grekiska: Χριστὸς, Christos) förekommer hos Josefus vid endast de två tillfällen då Jesus omnämns, vilket talar för att båda dessa passager är senare tillägg.

Man kan misstänka att Josefus medvetet undvek ordet Messias då detta var så starkt förknippat med den judiska önskan om militär befrielse från den romerska ockupationen och därmed avskytt också av den romerska maktsfären. Josefus utser faktiskt kejsar Vespasianus till Messias.[144] Han hävdar att judarna misstolkat den messianska profetian i 4 Mos 24:17–19 – att den som där sägs ska ”bli härskare över den bebodda världen” är Vespasianus. Trots detta indirekta utpekande av kejsar Vespasianus till Messias använder Josefus inte ordet Messias om Vespasianus.[145] Josefus verkar alltså ha skytt ordet Messias och kan av den anledningen inte gärna ha använt det i beskrivningen av Jesus och därmed inte heller ha skrivit Testimonium Flavianum i den form stycket föreligger, speciellt när han redan utsett Vespasianus till Messias/Kristus.

Mot detta går att invända att de passager i Testimonium Flavianum där Jesus utnämns till Messias kan vara senare tillägg. Ett annat argument går ut på att Josefus inte behöver ha sett negativt på Jesus. Whealey hävdar exempelvis att det är anakronistiskt att anta att Josefus som jude måste ha sett negativt på Jesus bara för att förhållandet mellan judar och kristna på 100-talet och senare var fientligt. Hon menar att så inte behöver ha varit fallet på Josefus tid och att Josefus därför kan ha skrivit de flesta av de positiva omdömen om honom som förekommer i Testimonium Flavianum.[146]

3) Josefus nämner inte Jesus i sitt äldre historieverk

Josefus nämner inget om Jesus i sitt äldre historieverk Om det judiska kriget (klart tidigast 78 vt). När han där på ett motsvarande sätt skriver om Pontius Pilatus och behandlar samma händelser saknas bland annat Testimonium Flavianum.[147] Om Josefus, såsom Whealey föreslår, såg positivt på Jesus och betraktade honom som en betydelsefull gestalt, varför skrev Josefus då inte om Jesus också i sitt första verk?[148][149]

Mot detta kan invändas att heller inte passagerna om Johannes döparen och Jakob förekommer i Om det judiska kriget. Vidare skulle kristendomen ha kunnat öka i betydelse i tiden mellan böckernas tillkomst och alltså först på 90-talet ha kvalificerat sig för att omnämnas.[150] En annan möjlighet är att Josefus använt andra källor för Judiska fornminnen och att Jesus omnämnts i dessa källor. För böckerna 18–20 förefaller de nya källorna dock i huvudsak ha varit romerska och inte ha sitt ursprung i det område Jesus ska ha verkat i. En ytterligare annan möjlighet är att Josefus hade ett annat motiv med sin senare bok – att han då i högre grad vände sig till icke-judar och därför fokuserade mer på populära rörelser och folk som förtryckts av det judiska ledarskapet.[151]

4) Testimonium Flavianum är orimligt kort

Om Josefus likväl ansett att Jesus var av betydelse och borde omtalas, varför skrev han då så relativt litet om honom?[152] Stycket om Johannes döparen[153] är exempelvis mer än dubbelt så långt och stycket som följer på Testimonium Flavianum och som handlar om Isiskulten och judendomen[154] och som dessutom är rätt trivialt är åtta gånger så långt. Stycket är av den längden att det skulle kunna infogas i en befintlig text utan att äventyra att den blev så lång att den inte fick plats i en bokrulle.[155] Det argument som brukar åberopas emot detta är att kristendomen ännu inte hunnit växa sig så stor när Josefus skrev att han ansåg sig föranledd att skriva mer.[156]

5) Testimonium Flavianum passar ej i sitt sammanhang

Styckena före och efter Testimonium Flavianum handlar alla om olyckor som drabbat judarna. Frånsett berättelsen om Jesus beskrivs alla händelser som olyckor, tumult och upplopp genom det grekiska ordet thoruboi, förutom vid ett tillfälle då ordet stasis med likartad betydelse används.[157][158] ´Som det ser ut förstör därför Jesuspassagen Josefus avsikt med denna avdelning som i övrigt visar på hur spänningen tilltar för judar runt om i riket.[159][160] En avrättning av en enskild person, tillika ledaren för den kristna sekten, skulle inte ha uppfattats som en olycka för judarna, framför allt inte av Josefus som var en jude väl förankrad i den judiska traditionen[161][162] och som identifierar sig som farisé.[163]

Mot detta kan invändas att fotnoten inte var uppfunnen vid denna tid och man tvingades därför göra plats för utvikningar inne i texten.[164][165] Fast när Josefus gjorde sådana utvikningar brukade han, i likhet med hur han gjorde i stycket efter Testimonium Flavianum, tala om att han gjorde en utvikning.[166] Vidare handlar omgivande berättelser om Pilatus tid vid makten[167] och Testimonium Flavianum befinner sig följaktligen både tidsmässigt och geografiskt på rätt ställe i texten.[168]

6) Meningen efter Testimonium Flavianum syftar på stycket före

Nästföljande stycke efter Testimonium Flavianum inleds med orden: ”Och ungefär vid denna tid var det ytterligare något förskräckligt som upprörde judarna”. Eftersom ”ytterligare något förskräckligt” (heteron ti deinon) måste syfta på något förskräckligt som Josefus just beskrivit och eftersom Jesu avrättning inte gärna kan ha varit något förskräckligt som upprörde judarna i allmänhet,[169] synes uttrycket syfta på stycket före Testimonium Flavianum där Pilatus sades ha genomfört en masslakt på judar.[170] Det var något förskräckligt som borde ha upprört judarna, och det verkar därför som om Josefus när han skrev att det vid denna tid var ytterligare något förskräckligt som upprörde judarna just hade avslutat beskrivningen av Pilatus massdödande av judar och att Testimonium Flavianum ännu inte förekom i texten.[171]

Mot detta brukar tre invändningar göras. (1) Att Josefus med ”ytterligare något förskräckligt” åsyftade allt annat förskräckligt som drabbat judarna och som han skrivit om tidigare, före Testimonium Flavianum,[172][173] (2) att Josefus verkligen skulle ha ansett att Jesu korsfästning var något förskräckligt som drabbat judarna,[174] eller (3) att Testimonium Flavianum i Josefus ursprungsversion innehöll en väsentligt annorlunda berättelse som verkligen beskrev något förskräckligt också för judarna, exempelvis ett upplopp som Pilatus slog ner.[175][176]

7) Testimonium Flavianum okänt fram till 300-talet

Ingen kyrkofader före Eusebios (100- och 200-talen, eller ens 300-talet) citerar eller hänvisar till Testimonium Flavianum. Vi känner till 14 kyrkofäder, däribland Origenes, vilka alla var verksamma före Eusebios tid (början av 300-talet) och sannolikt alla var bekanta med Josefus skrifter. Flera av dessa kyrkofäder citerade passager från Josefus, dock utan att hänvisa till Testimonium Flavianum.[177] Redan från tidig kristen tid var kristna upptagna med att försvara den kristna tron mot angrepp från meningsmotståndare, inte minst judar, och en hänvisning till en judisk källa som hyllade Jesus borde ha varit av intresse för dem alla. Louis Feldman pekar särskilt på Justinus Martyren som i mitten av 100-talet försöker bemöta påståendena att Jesus aldrig funnits och blott var ett kristet fantasifoster.[178] Enligt Feldman kunde det inte finnas något starkare argument för att bemöta sådana påståenden än att citera Josefus; en jude som föddes bara några år efter att Jesus dött.[179]

Invändningen mot tystnadsargumentet är att det är riskabelt att argumentera utifrån avsaknad av bevittnanden. Feldman håller med om den saken, men påpekar att när tystnaden är så massiv som i detta fall har argumentet ändå viss tyngd.[180] Vidare finns tecken på att kristna i allmänhet kände dåligt till Josefus och i synnerhet den andra halvan av hans Judiska fornminnen.[181] Det verkar dock osannolikt att om Josefus verkligen skrivit om Jesus, kunskapen om detta inte skulle ha spridit sig bland kristna. Andra argumenterar för att om de mest uppenbart kristna partierna tas bort kommer den återstående texten inte att stödja att Jesus var Guds son som uppstod från de döda. En sådan text skulle enligt detta synsätt endast visa att Jesus existerat, och i så fall skulle det inte ha funnits någon anledning för kyrkofäderna att åberopa stycket.[182] Detta motsägs dock av Feldman i resonemanget ovan. Därför spekulerar andra över att Josefus verk kan ha innehållit en annan och för kristna mindre fördelaktig version av Testimonium Flavianum[183] och att de av den anledningen inte fann något skäl till att hänvisa till passagen. Något egentligt textstöd för ett sådant antagande finns dock inte.[184]

8) En handskrift där Testimonium Flavianum saknades

Två patriarker i Konstantinopel förefaller ha haft en avskrift av Judiska fornminnen (möjligen samma avskrift) där Testimonium Flavianum inte ingick. Ca år 400 citerar Johannes Chrysostomos fyra gånger ur den bok av Josefus där Testimonium Flavianum förekommer utan att nämna stycket.[185] I stället skriver han att Josefus inte var en troende kristen.[186] I slutet av 800-talet sammanfattar Fotios i Bibliotheke (svenska: Boksamling) ett stort antal verk skrivna av andra, däribland Josefus författarskap,[187] men undgår att nämna Testimonium Flavianum trots att han återger passagerna om Jakob och Johannes döparen[188] och i övrigt verkar leta efter vad man skrivit om Jesus.[189]

Den vanliga invändningen mot detta är att om deras Josefustext i stället innehöll en version av Testimonium Flavianum som var mer neutral eller rentav fientlig mot Jesus skulle de av den anledningen ha avstått från att nämna passagen. Louis Feldman skriver däremot att det knappast finns någon kyrkofader som hetsar mer mot judarna än just Chrysostomos. Feldman anser därför att denne nästan oavsett hur Testimonium Flavianum sett ut borde ha haft svårt att undvika att hänvisa till passagen. Hade Josefus varit negativ till Jesus kunde Chrysostomos ha påtalat att detta var ett typiskt agerande från en jude. Hade Josefus varit positivt inställd till Jesus kunde Chrysostomos med hänvisning till Testimonium Flavianum ha påvisat att judarna var skyldiga till hans död.[190]

9) En innehållsförteckning utan Testimonium Flavianum

Nästan samtliga grekiska och latinska handskrifter av Judiska fornminnen inleds med en något skissartad lista över bokens innehåll.[191] Denna innehållsförteckning innehåller inte Testimonium Flavianum. Om innehållsförteckningen är gjord under den tid då kristendomen var i maktposition (början av 300-talet och framåt), är detta ett osvikligt tecken på att Testimonium Flavianum då saknades eftersom ett sådant stycke otvivelaktigt skulle ha omnämnts.[192]

Mot detta kan invändas att innehållsförteckningen kan vara äldre och till och med möjligen ha iordningställts av Josefus själv.[193] Och en jude i den äldsta tiden behöver inte ha gett Testimonium Flavianum någon speciell uppmärksamhet genom att omnämna det i sammanfattningen av bokens innehåll. Dessutom saknas mycket annat i innehållsförteckningen, även styckena om Jakob och Johannes Döparen.[194]

10) Testimonium Flavianum är en enhet och allt eller inget måste behållas

De klart kristna partierna som rimligen måste plockas bort för att trovärdiggöra att Josefus kan ha skrivit Testimonium Flavianum är logiskt länkade till de delar som blir kvar. Om exempelvis indikationen på att Jesus var Gud, ”om det nu är tillbörligt att kalla honom en man”, tas bort blir nästa mening, ”för han var en som gjorde förunderliga gärningar” märklig. Detta ”för” tycks vara en reaktion på ifrågasättandet att Jesus var en människa. Alltså, man kan verkligen fråga sig om Jesus var en människa för/eftersom han gjorde förunderliga gärningar. Om texten i stället löd att Jesus var en vis man för/eftersom han gjorde förunderliga gärningar blir den besynnerlig. I så fall borde författaren ha skrivit att Jesus var en vis man och gjorde förunderliga gärningar.[195] På samma sätt blir den påstått äkta meningen om ”de kristnas stam, uppkallad efter honom” ologisk om ”han var Kristus” plockas bort, ty endast genom informationen att Jesus kallas Kristus blir uppgiften om att kristna fått sitt namn av Kristus logisk. Av denna anledning behövs även de delar i Testimonium Flavianum som är tydligt kristna om man vill behålla en logiskt sammanhållen text. Och eftersom vissa partier i Testimonium Flavianum inte gärna kan ha skrivits av Josefus blir den logiska slutsatsen att han inte skrivit något alls av stycket.

Motargumenten till detta är att återstoden visst utgör en logiskt sammanhållen enhet,[196] eller att Josefus verkligen skrivit hela Testimonium Flavianum och därmed också de tydligt kristna delarna. De som argumenterar för den senare positionen anser att texten ska tolkas som mindre kristen än vad som normalt görs och kanske till och med fientlig mot kristendomen (i några fall till följd av att vissa ord antas ha blivit korrupta i transkriberingen), eller som om texten är avsiktligt dubbeltydig och kanske till och med ironiskt menad.[197][198][199] Carleton Paget påpekar dock att om man försöker omtolka de besvärliga passagerna för att bevara en logiskt sammanhållen text, blir till slut den kvarvarande texten mer eller mindre densamma som den bevarade versionen av Testimonium Flavianum och liknar därmed en ”fullständig interpolation”. I så fall skulle man enligt Paget kunna göra detsamma med andra trostexter i Nya testamentet, och bara skala bort allt som låter kristet i syfte att nå fram till en neutral text om Jesus.[200] Paget är tveksam till om detta är en metodologiskt säker metod och ifrågasätter Meiers och andras påstående att man utifrån språkliga överväganden kan avgöra vad som är ursprungligt och inte.[201]

11) Eusebios skapade Testimonium Flavianum

Ken Olson, i likhet med Solomon Zeitlin före honom,[202] argumenterar för att Eusebios skapade hela Testimonium Flavianum i början av 300-talet och att hans skapelse senare infogades i bok 18 av Josefus Judiska fornminnen. Till stöd för sitt antagande anför Olson språket i Testimonium Flavianum som enligt honom stämmer mycket bättre med Eusebios språkbruk än det gör med Josefus’. Utöver att Josefus aldrig använder vissa uttryck i Testimonium Flavianum som Eusebios använder, exempelvis ”och tiotusen andra ting”, ”de kristnas stam”, ”och ända till nu”, 8, 2 respektive 6 gånger var, drar Eusebios enligt Olson likartade slutsatser som de som förekommer i Testimonium Flavianum och resonerar i enlighet med de föreställningar som där kommer till uttryck. Olson anser att Testimonium Flavianum stämmer mycket väl överens med Eusebios språkbruk och med hans sätt att resonera.[203][204] Dessutom använder han Testimonium Flavianum för att bemöta påståenden att Jesus inte utförde några äkta underverk utan blott var en trollkarl och bedragare,[205] samma uppgift som Origenes bemötte hos Kelsos utan att hänvisa till Testimonium Flavianum.[206]

Olsons teori har kritiserats av James Carleton Paget, som bland annat menar att Eusebios i sin polemik inte använder de delar av Testimonium Flavianum som Olson bygger på,[207] och av Alice Whealey.[208] Whealey anser att Olsons paralleller till Eusebios inte alltid är exakta och när de är exakta avfärdar hon dem genom att exempelvis föreslå att ordet poiêtês, som i Josefus hela verk endast i Testimonium Flavianum förekommer i betydelsen av att utföra något, har haft en sådan påverkan på Eusebios att han efter att ha läst Testimonium Flavianum själv började använda ordet i den betydelsen, men då bara om Jesus och om Gud.[209] Olson menar dock att om man skulle anta att Eusebios har influerats så mycket av Testimonium Flavianum att han härmat dess språk (och dess kristologi), har man nästintill gjort det omöjligt att falsifiera äkthetshypotesen.[210]

Louis Feldman stöder Olsons resonemang och noterar att i den bevarade antika grekiska litteraturen förekommer uttrycken ”gjorde förunderliga gärningar” (paradoxôn ergôn poiêtês),[211] ”ända till nu” (eis eti te nun)[212] och ”de kristnas stam” (tôn christianôn … fylon)[213] endast hos Eusebios och i Testimonium Flavianum. Uttrycken förekommer aldrig annars hos Josefus eller hos någon annan överhuvudtaget.[214] Dessa uttryck tillhör dessutom de så kallade ”äkta” delarna av Testimonium Flavianum, vilka Josefus antas ha skrivit. Feldman anser att det i hög grad måste ha stört Eusebios, som kristen apologet och obändig försvarare av Jesus och den kristna tron, att ingen historiker före honom åstadkommit ens en summarisk skildring av Jesu liv och att detta kan ha motiverat honom till att skapa Testimonium Flavianum.[215] Feldman hävdar också att det finns skäl anta att en kristen som Eusebios skulle ha försökt framställa Josefus som mer välvilligt inställd till Jesus och att han därför mycket väl kan ha förfalskat en sådan redogörelse som den i Testimonium Flavianum.[216]

Goldbergs parallell med Emmausberättelsen

I en artikel från 1995 påvisar Gary J. Goldberg tydliga likheter i ord, uttryck och struktur i Testimonium Flavianum och i Lukasevangeliets berättelse om den uppståndne Jesus möte med två lärjungar på vägen till Emmaus (Luk 24:13–35).[217] Denna omständighet har använts både för att argumentera för att Testimonium Flavianum är skrivet av Josefus (som Goldberg gör och som andra håller med om)[218][219] och att det är en kristen förfalskning baserad på Emmausberättelsen i Lukasevangeliet. Goldberg har jämfört Testimonium Flavianum med Lukas 24:19–27 (med undantag för tillbakablicken i verserna 22–24). Han finner då 20 ord eller kluster av ord som förekommer i den grekiska texten i båda passagerna och 19 av dessa förekommer dessutom i samma ordning (undantaget är ”han var Messias”). Det enda i Testimonium Flavianum som saknar motsvarighet i Lukas 24:19–27 är uttrycken ”om det nu är tillbörligt att kalla honom en man”, ”ty han visade sig” och ”ända till nu har de kristnas stam, uppkallad efter honom, inte dött ut”. Inom varje kluster kan dock orden komma i omvänd ordning. Goldberg ger tre realistiskt möjliga förslag på denna överensstämmelse mellan texterna: (1) slumpen, (2) en kristen förfalskning gjord under inflytande av Emmausberättelsen i Lukasevangeliet, eller (3) att författaren av Lukasevangeliet och Josefus använt en gemensam källa.[220]

Goldberg anser att överenstämmelsen är för stor för att kunna tillskrivas slumpen och föredrar alternativ 3, att Josefus och författaren av Lukasevangeliet byggt på en gemensam kristen källa. Detta innebär i så fall enligt Goldberg att Josefus valde att inte ändra något i denna kristna källa utöver att anpassa språket något. Till stöd för detta anför Goldberg bland annat att det finns tecken på att Emmausberättelsen i Lukasevangeliet bygger på en redan existerande tradition; att där finns samstämmighet i vissa ovanliga uttryck, som exempelvis tritên echôn hêmeran i Testimonium Flavianum som bokstavligt betyder ”tredje dag havande”, och där en liknande konstruktion (där verbet heller inte verkar ha något uppenbart subjekt)[221] endast förekommer en gång i den kristna litteraturen, och då just i Emmausberättelsen i Lukasevangeliet 24:21, tritên tautên hêmeran agei (”denna tredje dag tillbringar”);[222] att Agapius version i vissa avseenden liknar berättelsen i Lukasevangeliet, samt möjligheten att Josefus byggt på samma kristna källa också i sitt omnämnande av Jakob.[223] Därmed skulle Josefus och författaren av Lukasevangeliet ha byggt på en gemensam kristen text, och kristna endast lätt modifierat Josefus text i efterhand.[224]

Richard Carrier håller med om att de strukturella likheterna mellan passagerna är för stora för att man rimligen kan tillskriva dem slumpen. I motsats till Goldberg menar han dock att detta visar att en kristen person konstruerat hela Testimonium Flavianum med Lukasevangeliet som förlaga.[225] Han avfärdar möjligheten att Josefus skulle ha byggt på en kristen källa som också författaren av Lukasevangeliet använde, med motiveringen att det i sig är osannolikt att Josefus okritiskt skulle ha övertagit en kristen trosbekännelse utan att göra några större innehållsmässiga ändringar. Carrier avfärdar också Goldbergs förslag om att Josefus byggt på samma kristna källa för båda omnämnandena av Jesus[226] med motiveringen att det senare Jesusomnämnandet är en oavsiktlig interpolation i Josefus verk.[227][228] Vidare noterar Carrier att Testimonium Flavianum innehåller ord och uttryck som är kristna, vilket också Goldberg visar,[229] och till och med typiska för Lukas, vilket enligt Carrier egentligen bara lämnar ett återstående rimligt alternativ. Eftersom Josefus knappast kan ha slaviskt kopierat en kristen text blir slutsatsen enligt Carrier att Testimonium Flavianum är en kristen komposition gjord efter Josefus tid med Lukasevangeliet som förlaga.[230]

Referenser

Noter

- ^ Steve Mason, Josephus and the New Testament, (Peabody: Massachusetts, 1992), s. 169–170.

- ^ Ken Olson, ”A Eusebian Reading of the Testimonium Flavianum” i Eusebius of Caesarea: Tradition and Innovations, ed. A. Johnson & J. Schott (Harvard University Press, 2013), s. 103; Alice Whealey, ”Josephus, Eusebius of Caesarea, and the Testimonium Flavianum”, s. 80, i Böttrich & Herzer, Eds., Josephus und das Neue Testament (Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2007).

- ^ Ken Olson, ”A Eusebian Reading of the Testimonium Flavianum” i Eusebius of Caesarea: Tradition and Innovations, ed. A. Johnson & J. Schott (Harvard University Press, 2013), s. 110, n. 44.

- ^ Alice Whealey, ”Josephus, Eusebius of Caesarea, and the Testimonium Flavianum”, s. 77, 101–105, i Böttrich & Herzer, Eds., Josephus und das Neue Testament (Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2007).

- ^ John P. Meier, A Marginal Jew: Rethinking the Historical Jesus, Vol 1: The Roots of the Problem (New York: Doubleday, 1991), s. 81, n. 41.

- ^ Judas från Galileen, Theudas, egyptern, en icke namngiven profet och Menahem.

- ^ Jona Lendering. ”Overview of articles on ‘Messiah’”.

- ^ John Dominic Crossan, The Historical Jesus: the life of a Mediterranean Jewish peasant (San Francisco: Harper 1991), s. 199.

- ^ Andreas J. Köstenberger, L. Scott Kellum, Charles L. Quarles, The Cradle, the Cross, and the Crown: An Introduction to the New Testament (Nashville: Broadman & Holman Academic, 2009), s. 105.

- ^ Josefus, Om det judiska kriget 6.312–313.

- ^ Alice Whealey, ”The Testimonium Flavianum in Syriac and Arabic”, New Testament Studies 54.4, 2008, s. 575.

- ^ Giorgio Jossa, “Jews, Romans, and Christians: from the Bellum Judaicum to the Antiquitates”, s. 333; i Sievers & Lembi (eds.), Josephus and Jewish history in Flavian Rome and Beyond (Leiden: E. J. Brill, 2005).

- ^ G. R. S. Mead, Gnostic John the Baptizer: Selections from the Mandaean John-Book, 1924, III The Slavonic Josephus’ Account of the Baptist and Jesus, s. 98.

- ^ Earl Doherty, Jesus: Neither God Nor Man – The Case for a Mythical Jesus (Ottawa: Age of Reason Publications, 2009), s. 548–549.

- ^ Robert Grant, A Historical Introduction to the New Testament (New York: Harper & Row, 1963).

- ^ Giorgio Jossa, “Jews, Romans, and Christians: from the Bellum Judaicum to the Antiquitates”, s. 331–342; i Sievers & Lembi (eds.), Josephus and Jewish history in Flavian Rome and Beyond (Leiden: E. J. Brill, 2005).

- ^ Earl J. Doherty,. The Jesus Puzzle: Did Christianity Begin with a Mythical Christ? (Ottawa: Canadian Humanist Publications), 1999, s. 222.

- ^ Josefus, Judiska fornminnen 18:116–119.

- ^ Josefus, Judiska fornminnen 18:65–80.

- ^ Richard Carrier, ”Origen, Eusebius, and the Accidental Interpolation in Josephus, Jewish Antiquities 20.200”, Journal of Early Christian Studies, (Vol. 20, No. 4, Winter 2012), s. 490.

- ^ E. P. Sanders, The Historical Figure of Jesus (New York: Penguin Press, 1993), s. 50–51.

- ^ James N. B. Carleton Paget, ”Some Observations on Josephus and Christianity”, Journal of Theological Studies 52:2 (2001), s. 579.

- ^ Eduard Norden, ”Josephus und Tacitus über Jesus Christus und eine messianische Prophetie”, i Kleine Schriften zum klassischen Altertum (Berlin 1966), s. 245–250.

- ^ Steve Mason, Josephus and the New Testament, (Peabody: Massachusetts, 1992), s. 164–165.

- ^ George A. Wells, The Jesus Legend (Chicago: Open Court, 1996), s. 50–51.

- ^ Marian Hillar, ”Flavius Josephus and His Testimony Concerning the Historical Jesus,” Essays in the Philosophy of Humanism Vol. 13, Houston, TX., 2005, s. 66–103. Se ”Flavius Josephus and His Testimony Concerning the Historical Jesus, s. 4.”.

- ^ Steve Mason, Josephus and the New Testament, (Peabody: Massachusetts, 1992), s. 166–167.

- ^ Josefus, Liv 2.

- ^ Leo Wohleb hänvisar till Judiska fornminnen 8.26ff, 10:24ff och 13:171ff, passager som alla avbryter den pågående berättelsen. Leo Wohleb, ”Das Testimonium Flavianum. Ein kritischer Bericht über den Stand der Frage”, Römische Quartalschrift 35 (1927), s. 151–169.

- ^ John P. Meier, A Marginal Jew: Rethinking the Historical Jesus, Vol 1: The Roots of the Problem (New York: Doubleday, 1991), s. 86.

- ^ Frank R. Zindler, The Jesus the Jews Never Knew: Sepher Toldoth Yeshu and the Quest of the Historical Jesus in Jewish Sources (New Jersey: American Atheist Press, 2003), s. 42–43.

- ^ Eduard Norden, ”Josephus und Tacitus über Jesus Christus und eine messianische Prophetie”, i Kleine Schriften zum klassischen Altertum (Berlin 1966), s. 241–275.

- ^ James N. B. Carleton Paget, ”Some Observations on Josephus and Christianity”, i Jews, Christians and Jewish Christians in Antiquity (Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2010), s. 225–226.

- ^ Steve Mason, Josephus and the New Testament (Peabody: Massachusetts, 1992), s. 165.

- ^ Josefus, Judiska fornminnen 18:60–62.

- ^ Richard Carrier, ”Origen, Eusebius, and the Accidental Interpolation in Josephus, Jewish Antiquities 20.200”, Journal of Early Christian Studies, (Vol. 20, No. 4, Winter 2012), s. 489–490.

- ^ John P. Meier, A Marginal Jew: Rethinking the Historical Jesus, Vol 1: The Roots of the Problem (New York: Doubleday, 1991), s. 86.

- ^ C. Martin, ”Le Testimonium Flavianum. Vers une solution definitive?”, Revue Beige de Philologie et d’Histoire 20 (1941), s. 422–431.

- ^ Gerd Theißen & Annette Merz, The Historical Jesus: A Comprehensive Guide (Minneapolis: Fortress, 1998), s. 72.

- ^ Robert Eisler, The Messiah Jesus and John the Baptist: According to Flavius Josephus’ recently rediscovered ‘Capture of Jerusalem’ and the other Jewish and Christian sources, 1931, s. 62.

- ^ David W. Chapman, Ancient Jewish and Christian Perceptions of Crucifixion; Wissenschaftliche Untersuchungen zum Neuen Testament; II ser. 244 (Tubingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2008), s. 80.

- ^ 1) Pseudo-Justinus, 2) Theofilos av Antiochia, 3) Melito av Sardes, 4) Minucius Felix, 5) Irenaeus, 6) Klemens av Alexandria, 7) Julius Africanus, 8) Tertullianus, 9) Hippolytos, 10) Origenes, 11) Methodios av Olympos, 12) Lactantius.(Michael Hardwick, Josephus as an Historical Source in Patristic Literature through Eusebios; Heinz Schreckenberg, Die Flavius-Josephus-Tradition in Antike und Mittelalter, 1972, s. 70ff). Till dessa kan också 13) Cyprianus av Karthago och 14) den grekisk-kristne apologeten Arnobius den äldre fogas. (Earl Doherty, Jesus: Neither God Nor Man – The Case for a Mythical Jesus, Ottawa: Age of Reason Publications, 2009, s. 538).

- ^ Justinus Martyren, Dialog med juden Tryfon 8.

- ^ Louis H. Feldman, ”Flavius Josephus Revisited: the Man, His writings, and His Significance”, 1972, s. 822 i Aufstieg und Niedergang der römischen Welt, 21:2 (1984).

- ^ Louis H. Feldman, ”Flavius Josephus Revisited: the Man, His writings, and His Significance”, 1972, s. 823–824 i Aufstieg und Niedergang der römischen Welt, 21:2 (1984).

- ^ Alice Whealey, ”Josephus, Eusebius of Caesarea, and the Testimonium Flavianum”, s. 74–75, i Böttrich & Herzer, Eds., Josephus und das Neue Testament (Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2007).

- ^ John P. Meier, A Marginal Jew: Rethinking the Historical Jesus, Vol 1: The Roots of the Problem (New York: Doubleday, 1991), s. 68, 79, 87.

- ^ Se Robert Eisler, The Messiah Jesus and John the Baptist: According to Flavius Josephus’ recently rediscovered ‘Capture of Jerusalem’ and the other Jewish and Christian sources, 1931, och s. 62 för Eislers hypotetiska rekonstruktion av Testimonium Flavianum i vilken Jesus framställs så negativt att Eisler kan tänka sig att Josefus också har skrivit passagen.

- ^ De enda texter som går att åberopa är de varianter som förekommer i Slaviska Josefus och dessa avfärdas numera nästa samfällt som medeltida förfalskningar. Se punkt 9 under argument för äkthet.

- ^ Louis H. Feldman, ”Flavius Josephus Revisited: the Man, His writings, and His Significance”, 1972, s. 822 i Aufstieg und Niedergang der römischen Welt, 21:2 (1984).

- ^ Johannes Chrysostomos, Predikan 76 om Matteus.

- ^ Fotios, Bibliotheke 47 (om Om det judiska kriget) och 76 & 238 (om Judiska fornminnen).

- ^ Fotios, Bibliotheke 238.

- ^ Exempelvis beklagar sig Fotios över att Justus av Tiberias i (det numera försvunna verket) Palestinsk historia “uppvisar judarnas vanliga fel” och inte ens nämner Kristus, hans liv och hans mirakler; Fotios, Bibliotheke 33.

- ^ Louis H. Feldman, ”Flavius Josephus Revisited: the Man, His writings, and His Significance”, 1972, s. 823 i Aufstieg und Niedergang der römischen Welt, 21:2 (1984).

- ^ Joseph Sievers, “The ancient lists of contents of Josephus’ Antiquities”, s. 271–292 i Studies in Josephus and the Varieties of Ancient Judaism”, eds. S. J. D. Cohen & J. J. Schwartz. Louis H. Feldman Jubilee Volume. Ancient Judaism and Early Christianity 67 (Leiden; Boston: Brill, 2007).

- ^ Louis H. Feldman, ”Introduction”; i Louis H. Feldman, Gōhei Hata, Josephus, Judaism and Christianity (Detroit 1987), s. 350.

- ^ James N. B. Carleton Paget, ”Some Observations on Josephus and Christianity”, Journal of Theological Studies 52:2 (2001), s. 556–557.

- ^ Louis H. Feldman, “On the Authenticity of the Testimonium Flavianum Attributed to Josephus,” i New Perspectives on Jewish Christian Relations, ed. E. Carlebach & J. J. Schechter (Leiden: Brill, 2012), s. 19–20.

- ^ Ken Olson, ”A Eusebian Reading of the Testimonium Flavianum” i Eusebius of Caesarea: Tradition and Innovations, ed. A. Johnson & J. Schott (Harvard University Press, 2013), s. 102–108.

- ^ Detta är John P. Meiers huvudsakliga ståndpunkt i hans inflytelserika bok A Marginal Jew: Rethinking the Historical Jesus, Vol 1: The Roots of the Problem (New York: Doubleday, 1991), s. 56–88.

- ^ I detta avseende går kanske Vincent längst genom att omtolka i stort sett alla problematiska passager i Testimonium Flavianum så att de ska ses som ironiska och egentligen negativa. A. Vincent Cernuda, “El testimonio Flaviano. Alarde de solapada ironia”, ”Estudios Biblicos” 55 (1997), s. 355–385 & 479–508. Se James N. B. Carleton Paget, ”Some Observations on Josephus and Christianity”, i Jews, Christians and Jewish Christians in Antiquity (Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2010), s. 229–233.

- ^ Bland dem som på senare år argumenterat längs dessa banor märks Alice A. Whealey, Josephus on Jesus, The Testimonium Flavianum Controversy from Late Antiquity to Modern Times, Studies in Biblical Literature 36. (New York: Peter Lang, 2003); ”Josephus, Eusebius of Caesarea, and the Testimonium Flavianum”, s. 73–116, i Böttrich & Herzer, Eds., Josephus und das Neue Testament (Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2007) och Serge Bardet, Le Testimonium flavianum, Examen historique, considérations historiographiques, Josèphe et son temps 5; (Paris: Cerf, 2002), s. 79–85.

- ^ Sammanfattat av Ken Olson i ”A Eusebian Reading of the Testimonium Flavianum” i Eusebius of Caesarea: Tradition and Innovations, ed. A. Johnson & J. Schott (Harvard University Press, 2013), s. 99.

- ^ Detta är precis vad Ken Olson demonstrerar med Apg 2:22–24 i ”Eusebius and the Testimonium Flavianum,” Catholic Biblical Quarterly 61 (1999), s. 308–309.

- ^ James N. B. Carleton Paget, ”Some Observations on Josephus and Christianity”, i Jews, Christians and Jewish Christians in Antiquity (Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2010), s. 236–237.

- ^ Solomon Zeitlin, “The Christ Passage in Josephus”, The Jewish Quarterly Review, New Series, Volume XVIII, 1928, s. 231–255.

- ^ Ken Olson, ”A Eusebian Reading of the Testimonium Flavianum” i Eusebius of Caesarea: Tradition and Innovations, ed. A. Johnson & J. Schott (Harvard University Press, 2013), s. 97–114.

- ^ Ken A. Olson, ”Eusebius and the Testimonium Flavianum,” Catholic Biblical Quarterly 61 (1999), s. 305–322.

- ^ Eusebios, Demonstratio Evangelica 3:5:105f. Ken A. Olson, ”Eusebius and the Testimonium Flavianum,” Catholic Biblical Quarterly 61 (1999), s. 309.

- ^ James N. B. Carleton Paget, ”Some Observations on Josephus and Christianity”, i Jews, Christians and Jewish Christians in Antiquity (Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2010), s. 203.

- ^ James N. B. Carleton Paget, ”Some Observations on Josephus and Christianity”, Journal of Theological Studies 52:2 (2001), s. 539–624.

- ^ Alice Whealey, ”Josephus, Eusebius of Caesarea, and the Testimonium Flavianum”, s. 73–116, i Böttrich & Herzer, Eds., Josephus und das Neue Testament (Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2007).

- ^ Alice Whealey, ”Josephus, Eusebius of Caesarea, and the Testimonium Flavianum”, s. 83, i Böttrich & Herzer, Eds., Josephus und das Neue Testament (Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2007).

- ^ Ken Olson, ”A Eusebian Reading of the Testimonium Flavianum” i Eusebius of Caesarea: Tradition and Innovations, ed. A. Johnson & J. Schott (Harvard University Press, 2013), s. 111.

- ^ Eusebios, Kyrkohistoria 1.2.23; Demonstratio Evangelica 114–115, 123, & 125.

- ^ Eusebios, Kyrkohistoria 1.11.8 (Testimonium Flavianum) & 2.1.7; Eclogae Propheticae, s. 168, rad 15.

- ^ Eusebios, Kyrkohistoria 3.3.2, 3.3.3.

- ^ “In total, then, three phrases—‘who wrought surprising feats,’ ‘tribe of the Christians,’ and ‘still to this day’—are found elsewhere in Eusebius and in no other author.” Louis H. Feldman, “On the Authenticity of the Testimonium Flavianum Attributed to Josephus,” i New Perspectives on Jewish Christian Relations, ed. E. Carlebach & J. J. Schechter (Leiden: Brill, 2012), s. 26.

- ^ “… it must have greatly disturbed him that no one before him, among so many Christian writers, had formulated even a thumbnail sketch of the life and achievements of Jesus. Consequently, he may have been motivated to originate the Testimonium.” Louis H. Feldman, “On the Authenticity of the Testimonium Flavianum Attributed to Josephus,” i New Perspectives on Jewish Christian Relations, ed. E. Carlebach & J. J. Schechter (Leiden: Brill, 2012), s. 27.

- ^ “In conclusion, there is reason to think that a Christian such as Eusebius would have sought to portray Josephus as more favorably disposed toward Jesus and may well have interpolated such a statement as that which is found in the Testimonium Flavianum.” Louis H. Feldman, “On the Authenticity of the Testimonium Flavianum Attributed to Josephus,” i New Perspectives on Jewish Christian Relations, ed. E. Carlebach & J. J. Schechter (Leiden: Brill, 2012), s. 28.

- ^ Gary J. Goldberg, “The Coincidences of the Emmaus Narrative of Luke and the Testimonium of Josephus,” Journal for the Study of the Pseudepigrapha 13 (1995), s. 59–77. Se ”The Coincidences of the Emmaus Narrative of Luke and the Testimonium of Josephus”.

- ^ Karl–Heinz Fleckenstein et al., Emmaus in Judäa, Geschichte-Exegese-Archäologie, (Brunnen Verlag, Gießen, 2003), s. 176.

- ^ James N. B. Carleton Paget, ”Some Observations on Josephus and Christianity”, Journal of Theological Studies 52:2 (2001), s. 593–594.

- ^ Gary J. Goldberg, “The Coincidences of the Emmaus Narrative of Luke and the Testimonium of Josephus,” Journal for the Study of the Pseudepigrapha 13 (1995), s. 59–77. Se ”The Coincidences of the Emmaus Narrative of Luke and the Testimonium of Josephus.”.

- ^ Se också James N. B. Carleton Paget, ”Some Observations on Josephus and Christianity”, i Jews, Christians and Jewish Christians in Antiquity (Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2010), s. 237.

- ^ Whealey hävdar att det är vanligt i kristna texter att Jesus sägs ha uppstått efter tre dagar i stället för på den tredje dagen, och att exempelvis de flesta handskrifter av Mark 8:31 har den läsarten; Alice Whealey, ”The Testimonium Flavianum in Syriac and Arabic”, New Testament Studies 54.4 (2008), s. 579, n. 21.

- ^ Josefus, Judiska fornminnen 18:63–64.

- ^ Gary J. Goldberg, “The Coincidences of the Emmaus Narrative of Luke and the Testimonium of Josephus,” Journal for the Study of the Pseudepigrapha 13 (1995), s. 59–77. Se ”The Coincidences of the Emmaus Narrative of Luke and the Testimonium of Josephus.”.

- ^ Richard Carrier, ”Eusebius, and the Accidental Interpolation in Josephus, Jewish Antiquities 20.200”, i Hitler Homer Bible Christ: The Historical Papers of Richard Carrier 1995-2013 (Philosophy Press: Richmond, California, 2014), s. 344.

- ^ Josefus, Judiska fornminnen 18:63–64; 20:200.

- ^ Richard Carrier, ”Origen, Eusebius, and the Accidental Interpolation in Josephus, Jewish Antiquities 20.200”, Journal of Early Christian Studies, (Vol. 20, No. 4, Winter 2012), s. 489–514.

- ^ Richard Carrier. ”Is This Not the Carpenter?”.

- ^ Gary J. Goldberg, “The Coincidences of the Emmaus Narrative of Luke and the Testimonium of Josephus,” Journal for the Study of the Pseudepigrapha 13 (1995), s. 59–77. Se ”The Coincidences of the Emmaus Narrative of Luke and the Testimonium of Josephus, s. 1–2”.

- ^ Richard Carrier. ”Jesus in Josephus”.

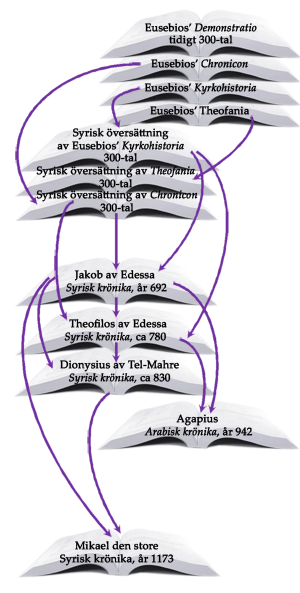

Francisco i Kalifornien. Hon kallar sig själv oberoende forskare. Whealey är mycket insatt, beläst och kunnig. Dessutom har hon, i motsats till flera av hennes kolleger, en debattstil utan polemiska övertoner. Det är framför allt hon som övertygande har visat att den arabiske 900-tals historikern Agapius använde samma källa som också 1100-talshistorikern Mikael den store använde, och att denna deras gemensamma syriska källa går tillbaka till den version av Testimonium Flavianum som kyrkofader Eusebios av Caesarea återgav och inte till den version som förekommer hos Josefus.

Francisco i Kalifornien. Hon kallar sig själv oberoende forskare. Whealey är mycket insatt, beläst och kunnig. Dessutom har hon, i motsats till flera av hennes kolleger, en debattstil utan polemiska övertoner. Det är framför allt hon som övertygande har visat att den arabiske 900-tals historikern Agapius använde samma källa som också 1100-talshistorikern Mikael den store använde, och att denna deras gemensamma syriska källa går tillbaka till den version av Testimonium Flavianum som kyrkofader Eusebios av Caesarea återgav och inte till den version som förekommer hos Josefus.