| Part 1 | |||

| ———— | ———— | ———— | ———— |

| Part 2a | Part 2b | Part 2c | Part 2d |

| Part 2e | Part 2f | Part 2g | Part 2h |

| Part 2i | Part 2j | Part 2k | Part 2l |

| Part 2m | Part 2n | Part 2o | Part 2p |

| Part 2q | Part 2r | Part 2s | Part 2t |

| ———— | ———— | ———— | ———— |

| Part 3a | Part 3b | Part 3c | Part 3d |

| Part 3e | Part 3f | Part 3g | Part 3h |

| Part 3i | Part 3j | ||

| ———— | ———— | ———— | ———— |

| Part 4 |

|||

| ———— | ———— | ———— | ———— |

| Excursus | |||

This is part 2n of the translation of my treatise Jesuspassagerna hos Josefus – en fallstudie into English.

Den svenska texten.

Notice that this is the second blog post today. The first part of the Syriac and Arabic translations is found here.

II. Testimonium Flavianum

The Church Fathers’ knowledge of the Testimonium

The Syriac and Arabic translations

The common sources of Michael and Agapius

Already Shlomo Pines realized that although Agapius’ version of the Testimonium is quite different from Michael’s (and everyone else’s); there are obvious similarities between them. Later on, also Alice Whealey and Lawrence I. Conrad compared the texts and found clear parallels to suggest a literary kinship.[136] There are several unique characteristics that Agapius and Michael share, which reasonably demonstrate that they both are relying on an older common source – such as that they both explicitly says that Jesus died, probably have the same expression that Jesus was thought to be the Messiah and give Josephus’ work a similar title.[137]

Agapius said himself that he based his chronicle on a now lost earlier Syriac chronicle written towards the end of the eighth century by Theophilus of Edessa (695-785 CE),[138] who belonged to the Syrian Christian Maronite Church. This in turn is supported by the fact that Agapius’ story begins at the Creation and ends around the year 780 CE, shortly before the death of Theophilus, but long before Agapius lived. Michael the Syrian on the other hand states as his source for the period c. 582–843, a chronicle by a certain Dionysius I of Tellmahre who was Patriarch of Antioch 818–848. In his chronicle Michael is quoting the preface to Dionysius’ chronicle, in which Dionysius acknowledged that he too drew on the work of Theophilus, the same Theophilus who Agapius refers to.[139] So in describing the events from the late sixth to the late eighth century, both Agapius and Michael relied on Theophilus’ eight-century Syriac chronicle – Agapius directly and Michael indirectly through Dionysius.[140] And when Agapius and Michael are compared, it can be shown that in spite of the fact that they both are dealing with the same period and are relying on the same source, Agapius’ text still is considerably shorter; which inevitably leads to the conclusion that Agapius paraphrases and shortens his source to a greater extent than Michael does.

Testimonium Flavianum tells about the fate of Jesus and covers the period of the first half of the first century. The question then is what source, or possibly sources, Agapius and Michael used in their descriptions of the earlier period, and then specifically for the first century, as they reasonably got the Testimonium from a source that deals with first century events? We know that Theophilus used Eusebius’ Chronicon and Ecclesiastical History (the Syriac translation) as his main sources for the period prior to Eusebius; that is before the fourth century.[141] This means that if Agapius and Michael both relied on Theophilus, their versions of the Testimonium is likely to be based on Eusebius’ version and not on Josephus’. However, it is far from certain that they relied on Theophilus also for the earlier period.[142]

Otherwise, one could conceive that Agapius and Michael also shared another source; a chronicle depicting the earlier period and that this chronicle perhaps was attached to their respective sources, Theophilus and Dionysius. Such a chronicle might be the oldest known of the Syriac chronicles, the one James of Edessa wrote in 692 CE and which also has not survived.[143] Another scenario is that they drew either directly on James or on someone else who in turn drew on him.

Otherwise, one could conceive that Agapius and Michael also shared another source; a chronicle depicting the earlier period and that this chronicle perhaps was attached to their respective sources, Theophilus and Dionysius. Such a chronicle might be the oldest known of the Syriac chronicles, the one James of Edessa wrote in 692 CE and which also has not survived.[143] Another scenario is that they drew either directly on James or on someone else who in turn drew on him.

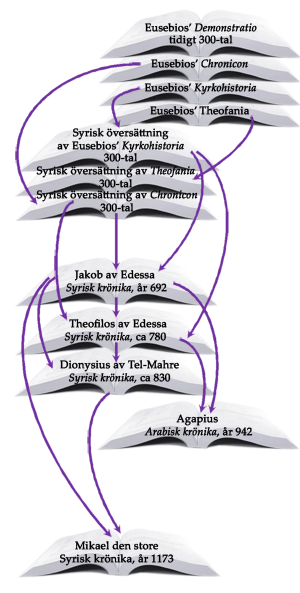

But the fact is that also James drew on Eusebius. His chronicle was a continuation of Eusebius’ Chronicle (Chronicon).[144] In any case, both Agapius and Michael apparently drew on a common Syriac source also for the Testimonium, as well as for the surrounding material, and that source in turn is based on a Syriac translation of Eusebius’ Ecclesiastical History. The course can simplified be described as illustrated in the image to the right (although in Swedish).

Eusebius’ books were very early translated into Syriac; so was for certain his Ecclesiastical History and Theophania. In both these translations the Testimonium is very close to the received text. And although we lack direct evidence, we still can assume that also Chronicon (where however the Testimonium does not exist) was early translated into Syriac. There are two more or less complete manuscripts containing the Syriac version of the Ecclesiastical History preserved – manuscripts referred to as MS A and MS B by scholars. MS B is paleographically dated to the sixth century, while MS A was written in 462 CE.[145] Furthermore, the oldest manuscript of the Syriac version of Theophania is dated to the year 411 CE.[146]

However, since both this manuscript and the one from 462 CE containing the Ecclesiastical History have many copying errors, it is obvious that these in neither case are the Syriac originals. The manuscripts probably are several transcripts away from the original translations. In addition, there is an Armenian translation of Eusebius’ Ecclesiastical History made in the early fifth century from the Syriac translation, which therefore must have been available already at that time.[147] The Armenian translation is most likely made from a fourth century Syriac manuscript. Also the Armenian text says without any reservation that he was the Christ. The literal meaning of ”Քրիստոս իսկ է նա” is “he is indeed Christ” or “Indeed, He is the one who is the Christ.”[148]

This has led to the assumption that the Syriac translation of the Ecclesiastical History and Theophania was made at the latest in the early fifth century, but more likely in the fourth century, and then perhaps as early as the first half of the fourth century. William Wright has suggested that the Ecclesiastical History was translated into Syriac as early as the time of Eusebius (he died in 340 CE) or shortly afterwards.[149] These Syriac translations of the Testimonium in Eusebius’ Ecclesiastical History and Theophania[150] follow the Greek text (accordingly also the text in Josephus) almost verbatim (if a translation can be said to be verbatim). Below is the Testimonium from the Syriac version of Eusebius’ Ecclesiastical History. The Testimonium is highlighted in the blue frame (the text is read from right to left).

The interesting thing is that Michael’s version shares many salient common characteristics with the early Syriac translation of Eusebius’ Ecclesiastical History. Michael could scarcely have translated the Testimonium from the Greek text of Eusebius or Josephus, as an independent translation for sure would bring a very different result. “The comparison of Michael’s vocabulary with that of the Syriac Historia Ecclesiastica confirms that Michael’s Testimonium must derive ultimately from an edition of the Syriac Historia Ecclesiastica”, Alice Whealey writes.

Michael therefore drew on the Syriac translation of Eusebius’ Ecclesiastical History (a translation probably made in the fourth century) but then in all likelihood indirectly. He probably got it from an older Syriac chronicler, who in turn drew on the Syriac translation.[151] The only essential differences between the Syriac translation (which closely follows the received text of the Testimonium) and Michael’s version, is that in Michael’s version Jesus “was thought to be” instead of “was” the Messiah and that Jesus’ death also is more emphasized. These two elements are also found in Agapius. In Agapius’ version of the Testimonium it says that “Pilate condemned Him to be crucified and to die”. Michael writes that “Pilate condemned him to the cross and he died”. Michael and Agapius are the only ones having this variant reading. However, one should bear in mind that according to the Quran Jesus never died,[152] and that it without any doubt could be important for Christians when confronted by Muslims to have a definitive statement from a Jewish historians that Jesus really died. [153]

As said before, another difference is that Michael has “was thought to be the Messiah”. Agapius instead writes that Jesus “was perhaps the Messiah”. The Arabic la‛alla means “perhaps”. But if now Agapius and Michael both drew on a common Syriac source, it is likely that this source had the same expression as Michael has, therefore mistavra (or mistabra). The Syriac mistavra means “thought to be” or “seemed to be”, but can also mean “perhaps”.[154] The Syriac original that Agapius drew on therefore probably had mistavra, and Agapius interpreted the word as “perhaps” and therefore translated mistavra into “perhaps”; in Arabic la‛alla.

It’s also quite obvious that Agapius does not quote the text he is draws on, but more summarizes it. This can be seen also in other passages; even the title of Josephus’ work is only approximately given.[155] Michael’s Chronicle is much longer than Agapius’ even though they cover the same period and Michael quotes long passages verbatim from his source.

Seemingly no one, not even Pines, appear to argue that Agapius used Greek sources. Even though Josephus’ Jewish War was translated into Syriac in the eight century, there is no evidence that by this time (that is the tenth century) the Antiquities of the Jews was translated into either Arabic or Syriac.[156] Agapius can reasonably not have drawn on Josephus’ Greek text, neither on any translation of his works. As far as one can judge, Agapius’ source for the Testimonium is, as he himself says, a Syriac text; then either Theophilus or some former Syrian chronicler who ultimately drew on the Syriac translation of Eusebius’ Ecclesiastical History. For those reasons Agapius does not rely on Josephus’ Antiquities of the Jews.

Agapius’ chronicle Kitab al-Unwan is thus an abbreviated historical account in the form of a paraphrasing translation of a Syriac chronicle into Arabic. In this, Agapius has also translated the Testimonium from Syriac into Arabic and then probably like he did with the rest, only approximately. But how could Agapius choose not to include the parts where Jesus is depicted as more divine? It is not easy to determine why a person does what he does. However, it is possible to examine how Agapius proceeded in other instances.

Agapius writes among other things about Jesus’ correspondence with king Abgar. The legend of Abgar, an evident tall story, is reproduced by Eusebius.[157] But since Agapius includes some details that do not occur in Eusebius or Michael, and the story in Agapius[158] shows apparent parallels both in language and content with a Syrian miracle story named The Teaching of Addai,[159] it is likely that he (also) drew on this fifth-century Syriac work, or possibly on a document very much like it. But king Abgar’s list of the miracles performed by Jesus, such as healing the blind, the paralyzed, the deaf, and so on – miracles that occur in both Eusebius and Michael, as well as in The Teaching of Addai – are missing in Agapius’ version. Apparently, he has omitted the miracles even though his source or sources had them. This is one example of how he downplays miracles.

The same thing can be seen in another fictitious letter by king Abgar, this time to the emperor Tiberius. There are no parallels with Eusebius and Michael, however, again with The Teaching of Addai. As in the previous example, Agapius’ version[160] is considerably shorter than the corresponding story in The Teaching of Addai; [161] and most importantly, the references to the miracles performed by Jesus when he was alive are removed. When Jesus in The Teaching of Addai is said to have “even restored the dead to life”, Agapius makes the return of the dead a result of Jesus’ crucifixion: “When they had crucified him … many of the dead came back to life and rose [from their tombs]”. One can of course speculate on why, but it is clear that Agapius on other occasions was playing down Jesus’ miracle-making. That the miracle-making is played down also in the Testimonium is therefore likely to be a result of Agapius himself playing it down and not a result of Agapius’ source having done it; especially since Agapius apparently drew on the same Syriac source as Michael and these elements appear in Michael’s version of the Testimonium.[162]

Because of this, it is apparent that Agapius himself removed the missing parts and that his version is but a downplayed version of what he found in his source. He appears to have done the same as many of today’s researchers want to do; he eliminated those parts of the Testimonium which he thought that Josephus reasonably could not have written. Furthermore, Agapius wrote probably for Muslim readers,[163] and for that reason did not want to exaggerate the miracles, but rather elaborated on the text so that it better suited Islamic readership. Alice Whealey on the other hand argues that he translated his chronicle for a Christian, because Muslims in general were not interested in Greek and Syriac texts.[164] However, this does not prevent that Agapius took his Muslim surroundings into consideration. Now, be that as it may. It is Agapius’ source that is interesting and not Agapius’ version. And the source is probably very similar to, if not identical with, the version we find in Michael; which better preserves the original text. Michael is thus the better witness! The question then is from where the source got the Testimonium?

What we think we know is as follows: Michael drew on other Syrian chroniclers, among those probably Theophilus and James, either directly or indirectly. Both of these latter drew on Eusebius for the early history before the time of Eusebius. Further, it can be established that Michael’s version of the Testimonium has a number of expressions and choices of words that are identical to the Testimonium found in the Syriac translation of Eusebius’ Ecclesiastical History; a translation probably done in the fourth century, perhaps while Eusebius was still alive. Michael has probably got his version of the Testimonium from some Syrian chronicler who in turn drew on the Syriac translation of Eusebius’ Ecclesiastical History. Moreover, there are certain peculiarities shared by both Agapius and Michael in their versions of the Testimonium, and these peculiarities suggest that they both drew on a common source, and also that these peculiarities existed in their common Syriac source.

The differences are that Jesus is explicitly said to have died and that he only was thought to be the Messiah. But the extant Syriac translation reproduces the received version, including that Jesus was the Messiah. In any case, Agapius’ loose paraphrase does not reflect any other source than the one Michael drew on. In that way, this is no independent witness to the Testimonium in Josephus, but everything comes from Eusebius. The only real difference between Michael’s and Agapius’ master on the one hand, and the received version in Josephus and Eusebius on the other, is whether Jesus was thought to be or simply was the Messiah.

Roger Viklund, 2011-03-19

[136] Alice Whealey, Josephus on Jesus: The Testimonium Flavianum Controversy from Late Antiquity to Modern Times (New York: Peter Lang, 2003). Lawrence I. Conrad, The Conquest of Arwâd: A Source-Critical Study in the Historiography of the Early Medieval Near East, Byzantine and Early Islamic Near East (Princeton, New Jersey, 1989).

[137] Alice Whealey, The Testimonium Flavianum in Syriac and Arabic, New Testament Studies 54.4 (2008) p. 582–585.

[138] Agapius, Kitâb al-‛unwân 2:2 [240].

[139] Michael the Syrian, Syriac Chronicle 10:20 [378].

[140] Alice Whealey, The Testimonium Flavianum in Syriac and Arabic, New Testament Studies 54.4 (2008) p. 576.

[141] Ken Olson, Agapius’ testimonium.

[142] Alice Whealey writes:

“Moreover, another Syriac chronicle that certainly used Dionysius’ chronicle, the Chronicle to 1234, does not closely follow either Agapius or Michael for the first century, and it entirely lacks a Testimonium.” (Alice Whealey, The Testimonium Flavianum in Syriac and Arabic, New Testament Studies 54.4, 2008, p. 576).

[143] Alice Whealey writes:

“One reason for favoring James of Edessa is that Michael claims that James made an abridgement of all the sources that he used that covered creation to the time of Heraclius (Michael the Syrian Praef. apud Chabot, Chronique, 1.2). This abridgement should probably be identified with James’ adaptation of Eusebius of Caesarea’s Chronicon (Michael the Syrian Chron. 7.2 [127–28] apud Chabot, Chronique, 2.253–5). Moreover, James of Edessa is frequently cited in the early part of Michael’s chronicle covering creation to the first century, while Theophilus of Edessa is never cited there. That James’ chronicle originally covered the period before Constantine is apparently also proven by extant fragmentary excerpts (E. W. Brooks, ‘The Chronological Canon of James of Edessa’, ZDMG 53 [1899] 261–327, esp. 263).” (Alice Whealey, The Testimonium Flavianum in Syriac and Arabic, New Testament Studies 54.4 (2008) p. 577, note 13)

[144] Testified to by Michael the Syrian in Syriac Chronicle, book 7.

[145] The National Library of Russia (Российская национальная библиотека) in Saint Petersburg (Cod. Syr. 1). At the beginning of the manuscript it is said that it was written by a certain Isaac in ”Nîsân, An Graecorum 773”, which corresponds to the year 462 CE. (William Hatch, An album of dated Syriac manuscripts, Boston, 1946, p. 54).

[146] London, British Museum, Add. MS. 12150. It is said in the manuscript that it was written in the “Second Teshrin, An Graecorum 723”. The second Teshrin is the name of the month of November, and according to the Greek chronology the year 723 corresponds to the year 411 CE. “The scribe’s name was Jacob and the manuscript was written in Edessa.” (William Hatch, An album of dated Syriac manuscripts, Boston, 1946, p. 52)

[147] Moses from the Armenian village of Khorena (Khoren, or Choren; ”Movses Khorenatsi”; probably lived in the fifth or the seventh century) testifies that Eusebius’ Ecclesiastical History was in a Syriac translation in the archives of Edessa, and that the Armenian monk and theologian Mesrop Mashtots (died in 441) made sure that this Syriac translation was translated into Armenian. This was done during Mesrop’s first major translation efforts before 430 CE. (Movses Khorenatsi, The History of Armenia 49:10).

[148] The Armenian version reads: ”∙Քրիստոս իսկ է նա.” Քրիստոս means Christ; իսկ means and, but, moreover, as in this case indeed, truly; է is a verb, then the third person singular present tense of եմ, i.e. is; նա means he, she or it. Accordingly it says: “Christ indeed is he”, or rather: ”he is indeed/truly Christ/Messiah.” This translation is confirmed in personal letters by Robert Bedrosian who writes: “The literal sense of the sentence is this: ‘Indeed, He is the one who is the Christ.’”; and by Bert Vaux who writes: “I would translate it literally as ‘he is indeed Christ’.”

[149] William Wright, A Short History of Syriac Literature (1894, reprint 2005) p. 61–62.

[150] The Testimonium from Eusebius’ Theophania. The work is preserved in only a Syriac translation, where the oldest surviving manuscript is as early as from the year 411 CE:

“There is nevertheless nothing to prohibit our availing ourselves even the more abundantly of the Hebrew witness Josephus, who in the eighteenth book of his Antiquities of the Jews, writing the things that belonged to the times of Pilate, commemorates our savior in these words: At that time there was a wise man named Jesus, if it be fitting to call him a man; for he was the worker of wonderful deeds and a teacher of men, of those who in truth accept grace, and he brought together many of the Jews and many of the pagans; and he was the messiah. And when, according to the example of the chief principal men among ourselves, Pilate put a cross on his head, those who formerly loved him were not silent; for he appeared to them on the third day alive, the divine prophets having said this and many other things concerning him. From then until now the sect of the Christians has not been wanting.” (Eusebius, Theophania 5.43b–44; from Ben C. Smith, Text Excavation, The Testimonium Flavianum)

[151] Alice Whealey, The Testimonium Flavianum in Syriac and Arabic, New Testament Studies 54.4 (2008) p. 579–580.

[152] From the Quran:

وَقَوْلِهِمْ إِنَّا قَتَلْنَا الْمَسِيحَ عِيسَى ابْنَ مَرْيَمَ رَسُولَ اللّهِ وَمَا قَتَلُوهُ وَمَا صَلَبُوهُ وَلَكِن شُبِّهَ لَهُمْ وَإِنَّ الَّذِينَ اخْتَلَفُواْ فِيهِ لَفِي شَكٍّ مِّنْهُ مَا لَهُم بِهِ مِنْ عِلْمٍ إِلاَّ اتِّبَاعَ الظَّنِّ وَمَا قَتَلُوهُ يَقِينًا

“And their saying: Surely we have killed the Messiah, Isa son of Marium, the messenger of Allah; and they did not kill him nor did they crucify him, but it appeared to them so (like Isa) and most surely those who differ therein are only in a doubt about it; they have no knowledge respecting it, but only follow a conjecture, and they killed him not for sure.”(The Qur’an, 4.157)

[153] G. A. Wells, The Jesus Myth, p. 216.

[154] Shlomo Pines, An Arabic Version of the Testimonium and its Implications (Jerusalem, 1971), p. 31; also p. 27, note 109.

[155] Earl Doherty writes:

”Pines (op.cit. [Schlomo Pines, An Arabic Version of the Testimonium Flavianum and its Implications], p.77–79) observes that both the Agapius and Michael the Syrian copies of their respective Josephus sources seem to have the title “On the Governance of the Jews.” (Earl Doherty, The Jesus Puzzle, Supplementary Article No. 16, Josephus on the Rocks, The Arabic Version)

But the Arabic text has actually “On the Evil of the Jews” and the translation into “On the Governance of the Jews” is based on the reconstruction of the text done by Shlomo Pines based on a quote of Agapius made by Al-Makin in the thirteenth century.

[156] Marian Hillar, Flavius Josephus and His Testimony Concerning the Historical Jesus (Center for Philosophy and Socinian Studies, 2005), p. 20.

[157] Eusebius writes:

“Abgarus, ruler of Edessa, to Jesus the excellent Saviour who has appeared in the country of Jerusalem, greeting. I have heard the reports of you and of your cures as performed by you without medicines or herbs. For it is said that you make the blind to see and the lame to walk, that you cleanse lepers and cast out impure spirits and demons, and that you heal those afflicted with lingering disease, and raise the dead. And having heard all these things concerning you, I have concluded that one of two things must be true: either you are God, and having come down from heaven you do these things, or else you, who does these things, are the Son of God. I have therefore written to you to ask you if you would take the trouble to come to me and heal the disease which I have. For I have heard that the Jews are murmuring against you and are plotting to injure you. But I have a very small yet noble city which is great enough for us both.” (Eusebius, Ecclesiastical History 1:13:6–8)

[158] From Agapius’ Kitâb al-‛unwân:

“On the part of Abgar the Black, to Jesus the physician who has appeared in Jerusalem. I have heard talk about you, of your science of medicine, your spiritual knowledge and what cures you perform of pains and diseases without drugs or remedies. My astonishment was large and my joy was extreme. And I said to myself that you must be, certainly, God or the Son of God, since you perform such acts. I request from you and invite you to come to me: perhaps you will cure the terrible disease with which I am afflicted. I have heard it said that the Jews want to kill you and to crucify you. I have a city, pleasant and beautiful, which will suffice for me and you to live there. There you will be in peace, good health and safety; and if it pleases you to grant my request, do it; and you will fill me with joy by what you will have done” (The Teaching of Addai, based on Vasiliev’s French translation, p. 474. I have set those parts in Agapius in bold that are missing in Eusebius and Michael. Reproduced by Ken Olson, Agapius’ testimonium)

[159] From The Teaching of Addai:

“Abgar Ukkama to Jesus the good physician who has appeared in the land of Jerusalem; my Lord, peace. I have heard concerning you and your healing that you do not heal with drugs or roots; it is rather by your word that you give sight to the blind, cause the lame to walk, cleans the lepers, and cause the deaf to hear; by your word you heal spirits, lunatics, and those in pain. You even raise the dead. So when I heard of the great wonders which you do I decided either that you are God in that you have come down from heaven and have done these things, or that you are the Son of God because you are doing all these things. Because of this I have written requesting that you come to me since I reverence you, and heal a certain illness which I have, since I believe in you. Furthermore I have heard that the Jews murmur against, persecute, and are seeking to destroy you. I have a small and beautiful city in which two might live in peace” (Translation by George Howard; SBL Texts and Translations 16, Early Christian Literature Series 4; Ann Arbor, Michigan: Scholars Press, 1981, p. 8–9. Reproduced by Ken Olson, Agapius’ testimonium).

[160] From Agapius’ Kitâb al-‛unwân:

“On behalf of Abgar, sovereign of Edessa, to Tiberius Caesar, sovereign of the Romans. Know, O King, that the Jews who are in your empire, have crucified the Messiah, though he did not deserve it, and had not done anything to drive them to it. When they had crucified him, the sun was darkened, the ground trembled, and many of the dead came back to life and rose [from their tombs], and there occurred many extraordinary things which no one had ever seen.” (Based on Alexander Vassiliev’s French translation of Agapius of Hierapolis, Kitab al-Unwan (Histoire universelle); ed. and trans. by Alexander Vasiliev; Patrologia Orientalis 7, 4; Paris 1912-13, p. 476. Reproduced by Ken Olson, Agapius’ testimonium)

[161] From The Teaching of Addai:

“King Abgar to our lord Tiberius Caesar, as follows: Although I know that nothing is hidden from your majesty, I write and make known to your powerful and great rulership, that the Jews under your authority who live in Palestine have gathered together and crucified the Messiah who was unworthy of death. This was after he had openly performed signs and wonders and had showed to them mighty wonders and signs. Thus he even restored the dead to life. When they crucified him the sun became dark, the earth quaked, and all creatures shuddered, and as from their own selves, all creation and its inhabitants waned at this affair. Your majesty knows, therefore, the right command he should give concerning the Jewish people who have done these things”. (Translation by George Howard; SBL Texts and Translations 16, Early Christian Literature Series 4; Ann Arbor, Michigan: Scholars Press, 1981, p. 77. Reproduced by Ken Olson, Agapius’ testimonium)

[162] Ken Olson, Agapius’ testimonium.

[163] Agapius dedicated his chronicle a certain Abu Musa ‘Isa, son of Husayn, about whom nothing else is known.

[164] Alice Whealey, The Testimonium Flavianum in Syriac and Arabic, New Testament Studies 54.4 (2008) p. 577–578.